For most of us, graduation means being thrown into the water—filing our taxes, cooking our own meals and learning the ropes of our dream field. The reality we’ve imagined while stuck in the four corners of our classroom slowly transforms before we can even get a hold of it. But being young and bright-eyed is a double-edged sword—knowing that we’re still carving our path is sometimes comforting.

But again, that’s for most of us. For young healthcare workers who’ve already had to battle the COVID-19 pandemic in their first years on the field, it’s more than diving into the deep end. It’s unforeseen and terrifying, like close to drowning.

Just a few years after graduation, these healthcare workers have already been tasked to save the world—literally. When we were kids, it was easy to write that wish on our slambooks. But doing it for real, with life at stake, is a different kind of skill.

And as if this huge responsibility isn’t enough, these frontliners also deal with discrimination and disregard. Just recently, Senator Cynthia Villar told them to work harder and be more passionate, after their plea for a timeout. She eventually took her statement back, clarifying that it’s the government that should work harder.

Meanwhile, President Rodrigo Duterte told nurses to rethink their career paths if they want higher pay. “Enter the police force. The salary is higher. If you remain a nurse outside, you only get about eight, nine, 10 [thousand pesos],” he said. As of writing, the Philippines has recorded 122,754 COVID-19 cases and a death toll of 2,168.

So in a time when your dreams are just starting, how do you cope when the world has suddenly depended on you? It’s true that not everyone has the same 24 hours. For these frontliners, every hour is a fight for survival.

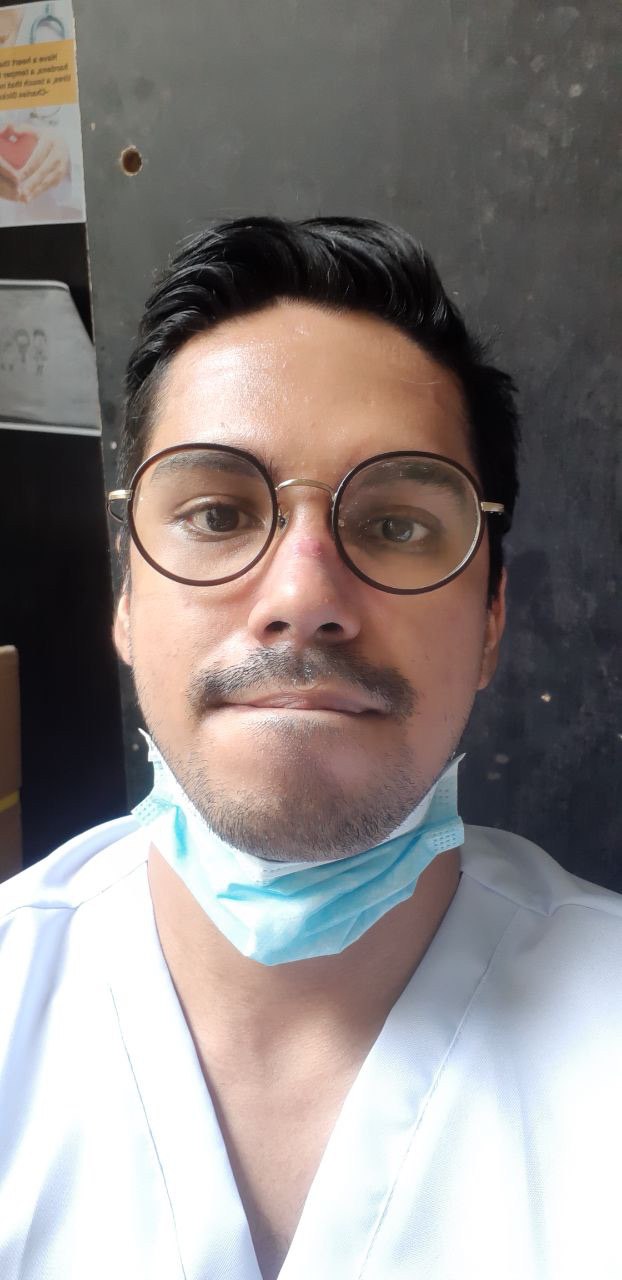

Jairus Cabajar, MD

The 28-year-old has been knee-deep in the healthcare field since his days as a public health student at University of the Philippines Manila. Jairus Cabajar—called Doc Jai by his Twitter followers—eventually pursued medicine at UP College of Medicine where he dedicated his last two years to hospital work. Now, his third year as an internal medicine resident in a government hospital marks his fifth year of seeing patients.

How was work like pre-pandemic?

Pretty average in terms of my personal life. But in terms of work, I’ve always thought that the problems we have now are pretty much the same as what he had before, just horribly magnified. It’s still a health system problem after all. Life pre-pandemic had a stress level of its own. Medicine is always a struggle.

How much has your work and life changed ever since COVID-19 happened?

It changed every aspect of my life. I went on a three-day duty cycle previously, and my entire schedule this year has been changed to accommodate attending to COVID-19 patients. A lot of hospital roles continue to change (even as you read this), and I could go on and on about it, but I would just bore you. I got used to making plans months ahead, just like anybody else. But because of the pandemic, I now plan one day at a time. I’m not really sure when this will end, so I avoid making long-term plans for now.

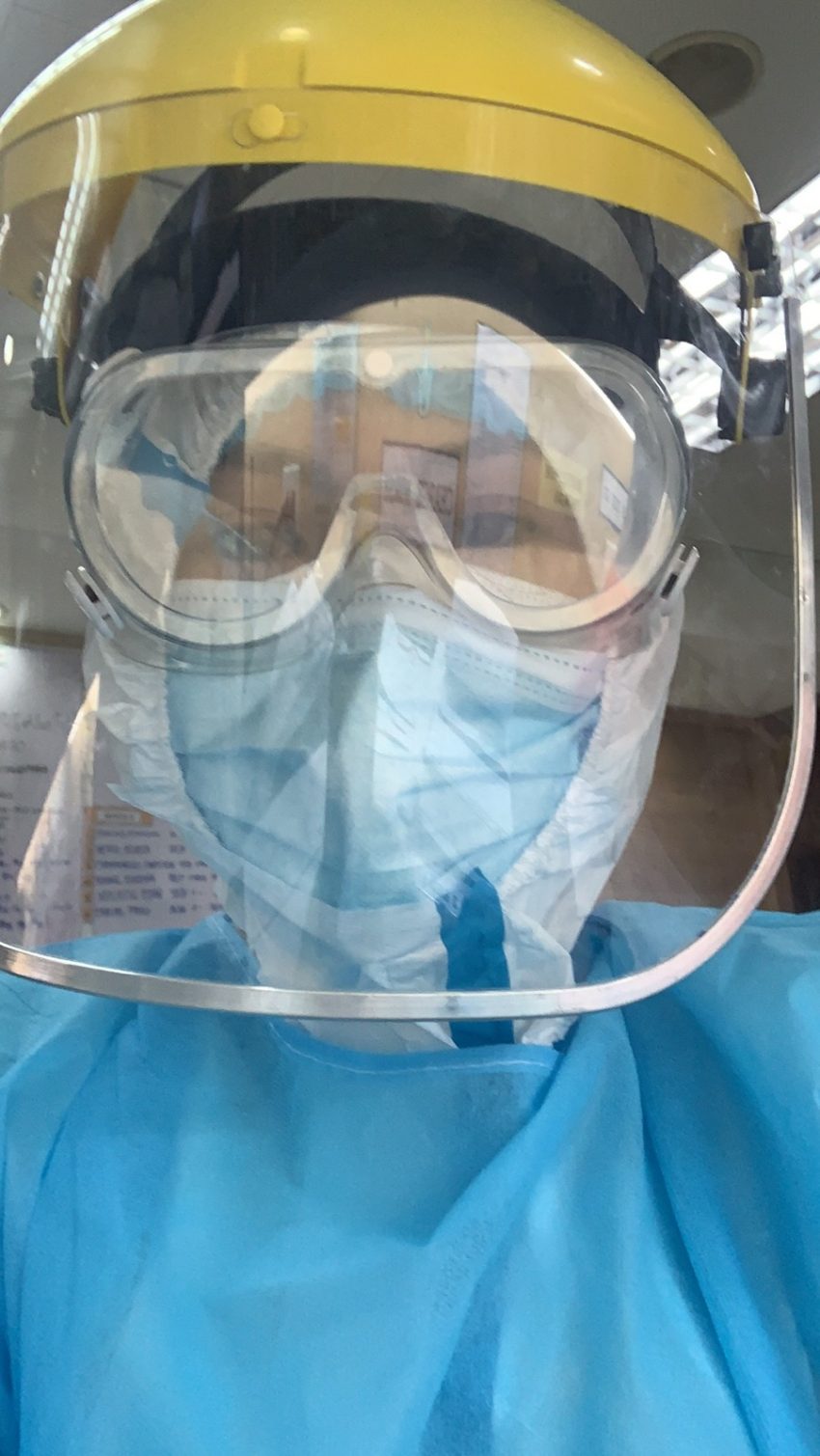

In terms of patient care, it’s really hard to connect with patients while you’re on level 4 PPE. I see them every day, and I get familiar with a lot of them but I wouldn’t be surprised if they can’t recognize me with all the masks and tapes covering my face. I wish I could establish more rapport with them, but there are limitations I can’t fix.

Doc Jai wearing a level 4 PPE

What goes in your day now with COVID-19 in the picture? Can you tell us about your usual routine?

I see my family whenever I’m on quarantine but when I’m on COVID-19 duties, I try my best to keep my distance from them. I just couldn’t take the idea of possibly giving them the virus. I don’t think I’ll be able to sleep if that happens.

When I’m on COVID-19 duties, my day starts at 5 a.m. I prefer not to drink lots of fluids prior because I expect that I would be wearing my PPE for at least eight hours. Seniors are usually tasked to man the ICUs where patients are in critical states. We are allowed to have breaks, but I prefer not to take them so I could watch over the patients and also not to waste any PPE because that would mean getting another set.

After my shift, I take another bath and eat my breakfast or lunch. I stay at the hospital because I’m supposed to be on-call whenever a problem comes up. After 24 hours, I go home, rest and then the cycle continues. It’s really hard to move while wearing our PPEs. I can’t say I don’t mind it now, I’m just used to the struggle of wearing it after all these months.

A snapshot of Doc Jai’s nose bridge bleeding from wearing N95

Have you encountered misconceptions about the healthcare system and/or workers ever since the pandemic?

Recently, frontliners have been asking for a timeout. Some people took this literally, thinking that we’re asking for a vacation. But no, it’s really just asking to recalibrate our direction during the pandemic. People forget that when the quarantine started, it was the health workers who continued to work and that will not change no matter how strict the quarantine gets.

Doc Jai standing in the middle of hospital beds, at a time when his hospital was preparing to become a COVID-19 referral center

Frontliners aren’t only physically exhausted during this pandemic. They’re also emotionally and mentally tired. How do you cope?

That’s true. Physical exhaustion is just one thing, and you get over it. But this pandemic is really emotionally and mentally tiring. Just imagine our anxiety whenever we enter a COVID-19 ward or ICU. We see how this virus takes lives and we are literally one PPE away from it. It’s exhausting to not know when this will end. But deep down inside, we know what we have to do.

We got a dog so I get to preoccupy myself. I spend lots of time doing home workouts. I talk to my colleagues. For some reason, it helps that we share the same sentiments— good and bad. It kind of disperses the negative energy and we get to laugh about mundane things. It helps that you have someone who understands what you’re going through.

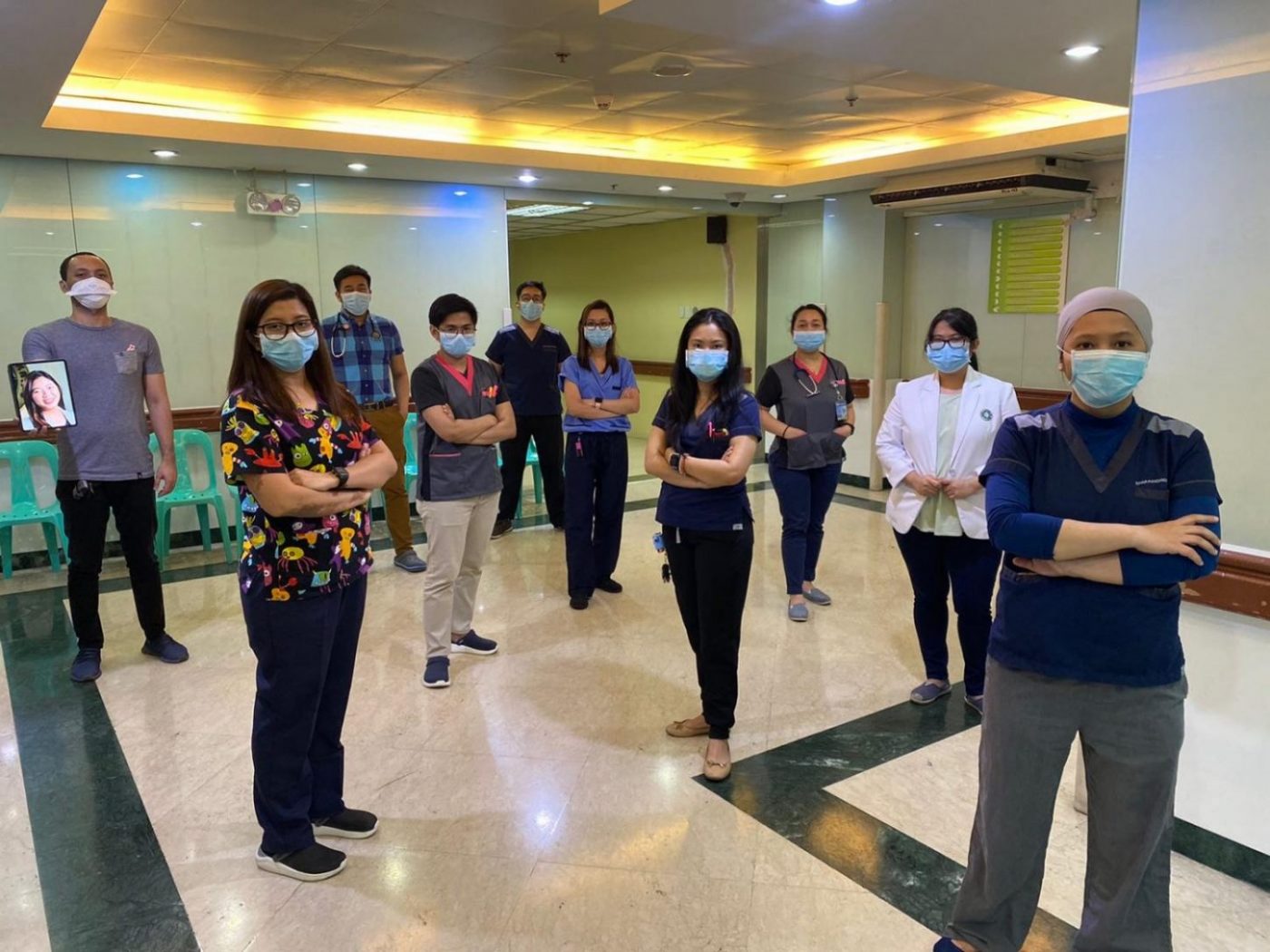

Doc Jai with his batchmates, whom he’s grateful for for keeping him sane

You’re still in your first few years in the field and you’ve already faced a pandemic. What are the things you’ll never forget from this experience?

Definitely, it makes you realize how much we need to change our healthcare system. You get to realize what needs to be fixed. You just can’t live the next years of your life not trying to change whatever needs to be changed. This can’t go on.

I’ll never forget about the patients. They are isolated, and the nurses and doctors in white PPEs are all that they have. We’ve become some sort of family to them. We celebrate recoveries, we laugh at how uncomfortable swab tests are (hoping it will finally turn out negative), and we mourn deaths together.

You get to realize what needs to be fixed. You just can’t live the next years of your life not trying to change whatever needs to be changed. This can’t go on.

What do you want to see in our healthcare system now and in the future? Any insights you learned and are still learning that could serve us better in the future?

I just want my patients to have what they deserve—and this includes patients I’ve handled before the pandemic. We started rough in terms of PPE, manpower and testing. Five months into the pandemic, we still are figuring things out. The problem with COVID-19 is that it isn’t the only disease, and healthcare for non-COVID-19 patients are affected, as well. I don’t wish to suffer from another pandemic but if it happens, I hope that we respond better. I hope that we get to have leaders who empower the Filipino people, instead of making them even more divided.

What are your personal wishes?

I just want this to be over, to be honest. But I don’t want to go back to “normal.” I want a normal where people don’t beg for rights and leaders truly serve the Filipino people.

Doc Jai with his co-residents

What issues do healthcare workers struggle most with that outsiders may not be aware of?

That we are human beings just like anybody else. We have shortcomings, we have weaknesses, we have faults. We are usually painted as heroes and I appreciate that. But we can’t always live up to that expectation. We have a sense of service but we do not have superpowers. We need the support of the government for us to do the job that we signed up for.

Margarette Pajanel, MD

As a senior medical resident in a government hospital, the 29-year-old Margarette goes on 24-36-hour duties, conducts rounds on patients, updates consultants on the patients’ status after checking up on them and manages accordingly. She’s been exposed to the healthcare field ever since clerkship, dating back to 2014.

How was work like pre-pandemic?

Work pre-pandemic was more certain. Schedules are predictable. And it’s easier to move and breathe around.

How much has your work and life changed ever since COVID-19 happened?

Due to COVID-19, work and life got monotonous. It’s almost always all COVID-19. We no longer see other cases as much as we used to pre-COVID-19.

What goes in your day now with COVID-19 in the picture? Can you tell us about your usual routine?

Life routine has become hospital-dorm-hospital-dorm. We also no longer go home to our families for fear of being the one giving them COVID-19.

Discrimination is also something we deal with and with the perspective that this pandemic has blown out of proportion is our fault.

Have you encountered misconceptions about the healthcare system and/or workers ever since the pandemic?

It’s really tough on all of us, not just for the frontliners and the ones in healthcare. From our perspective, it’s mentally, emotionally and physically exhausting because we have to stay in a hazmat for hours and be the one to deliver the bad news to relatives of patients, who they can’t even be with during their final moments. Discrimination is also something we deal with and with the perspective that this pandemic has blown out of proportion is our fault.

How do you cope given the physical, mental and emotional exhaustion?

I try to cope by taking things one day at a time, and doing barre and yoga when I can.

Dr. Pajanel wearing level 4 PPE

You’re still in your first few years in the field and you’ve already faced a pandemic. What are the things you’ll never forget from this experience?

I will never forget the pain of isolation this pandemic has put everyone through. Relatives are allowed to be with their patients, so they can see the status of their patients. COVID-19 changed all that. It’s all the more painful for the relatives (and the patient) to not have someone with them during crucial times, and not knowing and seeing their patient’s status.

What do you want to see in our healthcare system now and in the future? Any insights you learned and are still learning that could serve us better in the future?

Honestly, I think good open communication between the medical communities and economic managers will greatly benefit this country. We can save more lives and cushion the effect on the economy. I can only wish that this should’ve been done from the start.

What are your personal wishes?

Personally, I wish for people to be more critical and open-minded. Always assess and reassess facts given, and not be blinded by biases. Healthcare is political, unfortunately.

Dr. Pajanel with her fellow healthcare workers

Gillian S., RN*

Gillan* works as a nurse in the COVID-19 wards of a government hospital, battling eight-hour shifts with seven days of duty and seven days off. At 22 years old, she does patient assessment, medication preparation and administration. She also attends to patient needs like nutrition (feeding the patient, hooking the patient to Total Parenteral Nutrition or TPNs), hygiene (bathing the patient, changing diapers and oral care), social needs (connecting the patient with their families through video calls) and patient education—letting them become aware of their medications and illness.

How was work like pre-pandemic?

I was in the research field pre-pandemic. Work was basically writing research chapters, data collection and collation, and transcribing interviews—mainly doing research work at home and attending meetings one to two times a week.

How much has your work and life changed ever since COVID-19 happened?

A lot. Being a nurse researcher and being a bedside nurse are two different things. From sitting at home reading tons of articles and journals to standing, walking and running in the wards taking care of patients for eight hours is really a huge shift.

What goes in your day now with COVID-19 in the picture? Can you tell us about your usual routine?

Usual cycle includes waking up, going to work, hoping na walang codes and intubations, magtawid ng eight-hour shift na minsan nine hours pa nga kasi mag-to-toxic ang patient. Tapos noon, uuwi. Maliligo, kakain ng free food galing sa dietary or galing sa donations. Mag-so-social media nang kaunti tapos matutulog na. Then repeat the cycle for seven days. May day off naman in between seven days duty in which I spend just sleeping or watching movies.

With COVID-19 in the picture, work feels a lot heavier. It’s not only because of the level 4 PPEs that we use and the threat that we could also get infected ourselves but also [because] we cannot get a nice break from all of these. Walang social interactions. Walang malls, walang entertainment. ‘Yung week off na seven days, parang nakakulong lang kami sa accommodation. Hindi ako umuuwi sa bahay namin because I fear that I might infect my parents who are in advanced age na rin.

Nurse Gillian with her fellow healthcare workers

Have you encountered misconceptions about the healthcare system and/or workers ever since the pandemic?

That the healthcare system can accommodate the surge of patients. Yes, we have beds. But manpower? Super short-staffed kami. ICUs ay two to three patients per nurse. Wards naman, eight to 10 patients per nurse. Oo, may beds, pero ‘yung mag-aasikaso, mga naka-quarantine, mga infected na.

Frontliners aren’t only physically exhausted during this pandemic. They’re also emotionally and mentally tired. How do you cope?

During my off weeks, I try to interact with my family and friends. Kahit na via chat or video call lang, malaking bagay na rin ‘yun for me. Although I want to be physically present next to them, wala akong magawa kasi hindi ko naman kayang i-risk ‘yung health nila para lang ma-satisfy ‘yung pagka-miss ko sa kanila. Also, exercise really helps me to be sane during off weeks. Aside from its immunity benefits, entertainment na rin siya for me.

Sobrang nakakaubos ng lakas kapag araw-araw kang mag-a-assist ng nag-co-code at pagtapos mag-code, ibabalot ang katawan, kukunin, tapos may i-a-admit ulit sa bed na iyon dahil bumabaha ng pasyenteng pending sa emergency room.

You’re still in your first few years in the field and you’ve already faced a pandemic. What are the things you’ll never forget from this experience?

The fuck-up. Na imbis na tulungan tayo ng gobyernong ito, mas lalo pa tayong nilulugmok sa kahirapan. Hindi lang nila alam kung gaano kahirap ang sitwasyon sa mga ospital dahil wala sila mismo doon. Kung gaano kahirap mag-inform ng relative na malaki ang posibilidad na matubuhan ang kapamilya nila, na hindi nila makita at makausap bago pa mawalan ng malay at manghina.

Sobrang nakakaubos ng lakas kapag araw-araw kang mag-a-assist ng nag-co-code at pagtapos mag-code, ibabalot ang katawan, kukunin, tapos may i-a-admit ulit sa bed na iyon dahil bumabaha ng pasyenteng pending sa emergency room. Kung maaga lang sanang naagapan ito, hindi na sana hahantong sa puntong ito ang Pilipinas. Sobrang sayang. Sobrang sayang ng mga buhay.

Nurse Gillian with her fellow healthcare workers

What do you want to see in our healthcare system now and in the future? Any insights you learned and are still learning that could serve us better in the future?

Primary healthcare should be prioritized. Interventions should be focused on the root cause of the problem instead of giving band-aid solutions. Dahil kung ganoon din lang, ma-e-exhaust at ma-e-exhaust ang resources ng Pilipinas nang walang na-so-solve na problema.

Primary healthcare should be prioritized. Interventions should be focused on the root cause of the problem instead of giving band-aid solutions.

What are your personal wishes?

That all this may come to an end. Everyone’s exhausted already.

What issues do healthcare workers struggle most with that outsiders may not be aware of?

One of the issues that healthcare workers struggle the most with that the outsiders may not be aware of is that the healthcare workers are discriminated against in the real world.

*Name has been changed as requested by the interviewee.

Read more:

We’re calling 2020 a gap year since there’s no undo button

Cinemalaya 2019’s ‘Edward’ reveals the sorry state of public healthcare

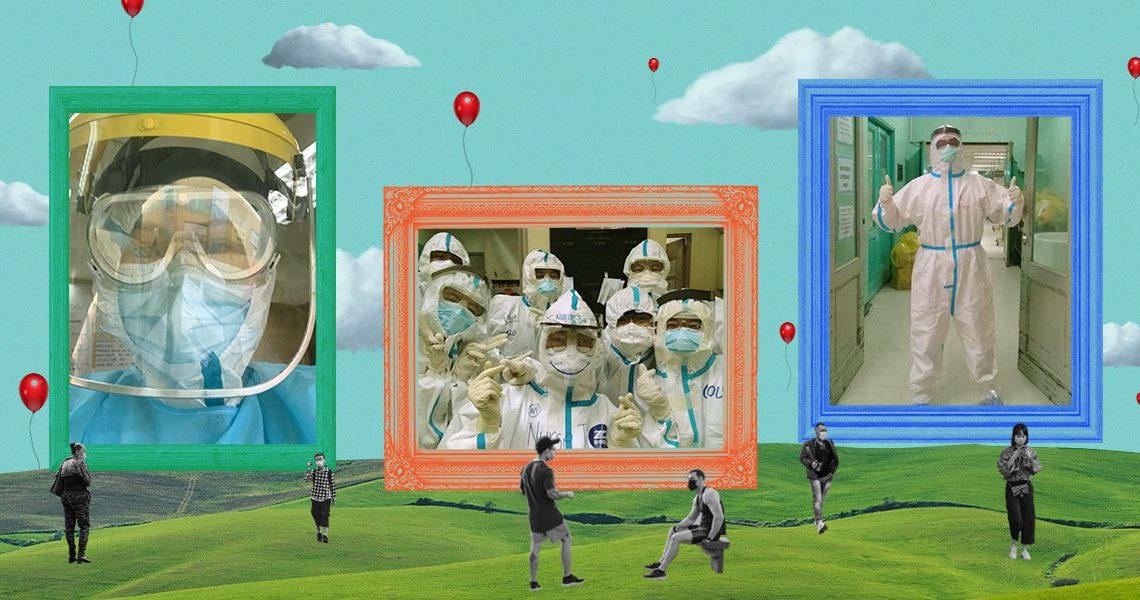

Photos courtesy of the interviewees

Art by Yel Sayo

Comments