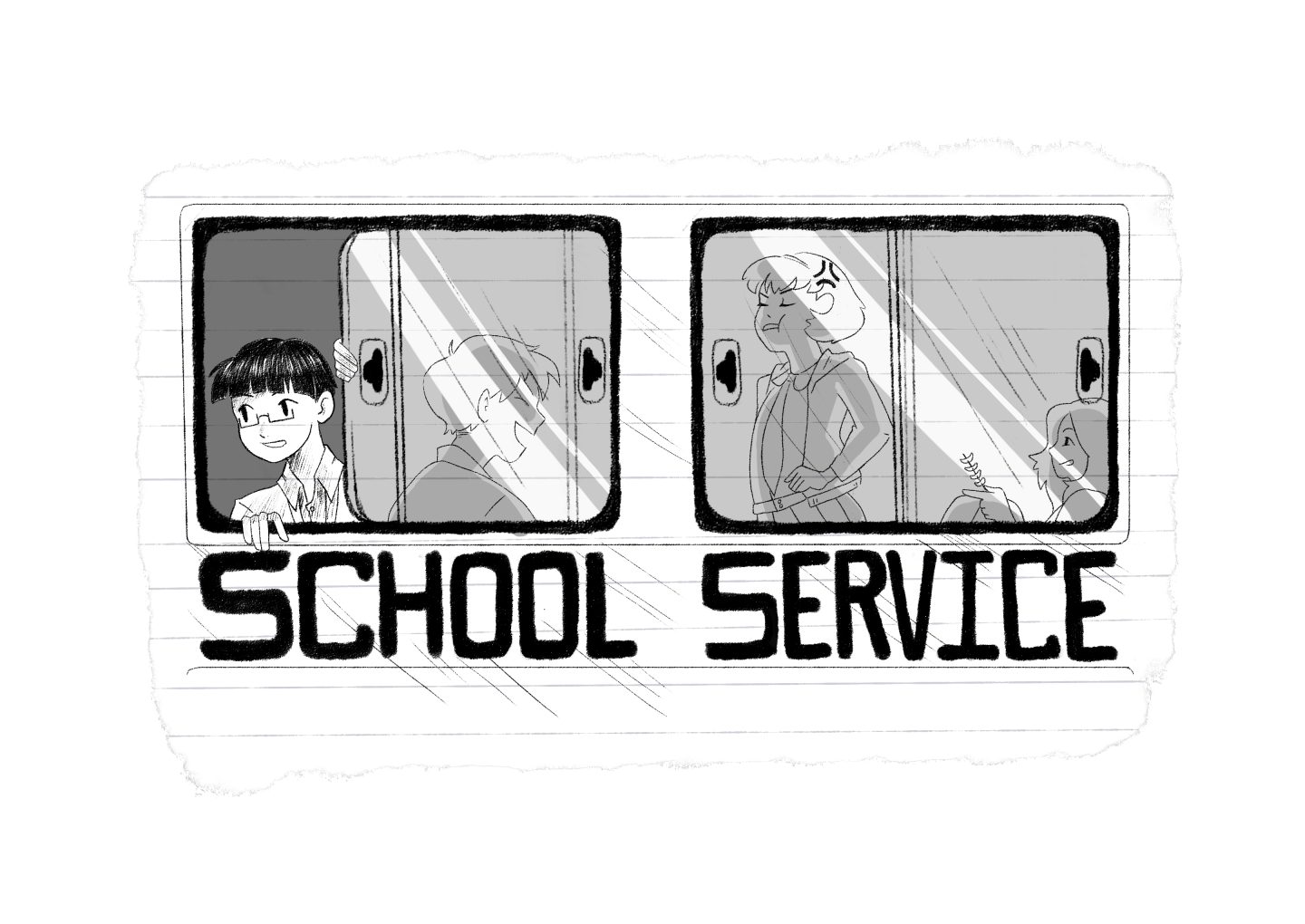

The school bus, or the school service, carries a slice of our childhood. From early morning conversations yielded with fellow students on the way to school, to after-school mischief that made moments more striking than the JS Prom or basketball matches, the school service is more than a vehicle to those who spent years in it. With unforgettable memories at hand, four writers recall stories of innocence, friendship, and mystery—all happened in the school service.

Read more: What I realized after re-reading my high school yearbook

Trust issues

by Yazhmin Malajito

When I was in grade school, I called my school bus—actually, it was a jeep—Mariposa because of the colorful words written on the “forehead” of the vehicle. The name the signage bore was usually that of the jeepney owner’s kin, but I didn’t know who Mariposa was exactly. Mariposa, the jeep, was unusually long. It could accommodate up to 25 students. It was fast. It was not as noisy as other jeeps. And one day, it ran over a child on our way to school.

We felt the bump a millisecond before the sudden brake. For a few seconds, everyone held their breaths. I remember my knees were shaking.

I’m not sure if I saw the incident or if I just conjured a scenario according to what Kuya Ronald and my “ka-service” said. But what happened was this: The boy was crossing the six-lane Governor’s Drive just past Trece Martires City’s arc. It was an accident-prone area. He was running with a few friends, or siblings—or was it a guardian and an older sibling? I’m not sure anymore. He was the last to cross—maybe his limbs were too short—when Mariposa hit him.

Kuya Ronald carried the poor child inside Mariposa. His companions also climbed in. The boy was crying. Although there wasn’t a lot of blood, his knees were bent at a weird angle. The impact wasn’t that intense, I thought.

Looking back and contemplating this memory, almost forgotten because it happened so damn fast, I think that this may be one of the fragments making up my trust issues. Imagine a school service—a vehicle supposed to protect kids—almost killing a child. Even before this incident, Mariposa wasn’t always a place of refuge. Physical bullying happened there. Kuya Ronald also touched my ass a couple of times, but let’s not talk about that.

We visited the boy (a detour before we went to school) a few months later and he was doing better, thanks to Mariposa’s swift trip to the hospital.

Read more: How I fell in love with makeup at all-girls Catholic school

The secret club

by Jelou Galang

“Walang hiya ka!”

One, two, three. Pause. The famous teleserye line once found its way inside a fire brick red multi-purpose vehicle. I stayed here for five years, thanks to Ate Arlene and Kuya Monching’s kindness.

“Ako pa? Ako pa?”

No, we weren’t brawling—even if you’d think third-grade kids would actually be able to pull each other’s hair already. The teleserye line remains a teleserye line in our school service. Wearing double-layered uniforms in the scorching Manila heat, with smeared iskrambol slowly dripping from our lips, we re-enacted a scene from Maria Flordeluna, props included. One was a flower we may or may not have picked from the school garden.

A big chunk of my childhood rests in the moving entity that started its engine once the last bell rang. It saw countless elementary kids trying to grow up fast, and high schoolers wanting to be kids again.

It’s striking how we got together just two times a day: before and after school. What more? How my servicemates saw what my classmates didn’t. Of course, it was the same for them.

It was 5:45 a.m. and our street was flooded. I remember being carried by my then-alive tito from our house to the service. The tallest in the gang said I looked like a baby. Everyone laughed.

The laughter was louder when my closest service pal, Chelsea, turned tomato red after my servicemates read her entry in my slambook. “Josh,” she had written in the secret crush portion. “It’s not a secret now,” our resident bad boy blurted out. But who were we fooling? Our school service was like a secret club. We’d slide our windows and slam our door if someone hijacked the fun.

But we’d open the door sometimes for the little things: When the manang finally got to restock the pink Hai candy. When there was a new set of two-peso rubber rings. Or when the squidball cart beside us had a new batch ready. If only our school nuns had seen that one time we had a literal street food fiesta inside our moving crib. But the school didn’t see us there. I guess that was the best part.

We cried, sang, screamed, danced. We shared personal stories our homeroom subject would never hear. We played games our teachers wouldn’t want to see. There were Pogs, Teks, Pokémon cards. And of course, there were re-enactments from our favorite shows, from Agua Bendita to Bituing Walang Ningning.

“Walang hiya ka!”

The teleserye line remains a teleserye line. But our school service was also a show.

Before and after school were the only times we got together—and the only times we interacted with each other. Inside the school, we were like strangers. There was no trace of the secret club anywhere else outside the service.

I guess there was a certain humiliation we felt at school—a limiting, conservative environment—when we’d see each other, thinking that we knew everyone’s true, uncontained selves.

But just like all great friendships, ours would continue like it had never been cut off, right after the last bell of the day. “Mukha kang itlog,” one would say, and the club would start its session again. We were truly walang hiya.

Read more: 5 hidden bookstores in Manila that fit your back to school budget

Pinwheels

by Zofiya Acosta

When you’re a child, mundane events turn into paranormal phenomena. A gust of wind changes the direction of a pinwheel’s flight, and schoolchildren gasp and scream because it means their service jeep is haunted.

In second grade, I announced to my mom that I was going to ride a service to school. That’s what we called the commercial jeepneys that doubled as school services. In the metro, I see school services painted yellow and black to differentiate them from the normal jeeps, but in the province where I lived, they were one and the same. I wanted to spend more time with my best friend, who rode the same jeep. My mother and my papang were the only ones who would drive me to school before then.

Riding the service was fine. It felt nice having more time with other kids (barring my infant brother, my only company at home was adults), and it was fun to talk about the important topics of the time: Do you like ABS or GMA? Who will Alwina choose in Mulawin? Which ending of Sana’y Wala Nang Wakas did you vote for?

It was the pinwheel that changed everything. A few vendors had set up shop on the street in front of the school. Maybe unknown to them, their wares became the arbiters of cool at my school. When they sold tiny boxed spiders, all the boys started playing death matches with the poor eight-legged creatures. When they sold goldfish, I became a fish mom and housed a little orange fish in an aluminum bowl and cried in the morning when I discovered the fish had jumped out while I slept.

That month, it was the pinwheel. Kids all over the school had the little axle toy. They would spin them around to see where they would fly. My friends and I would bring ours to the service, and we would spin these little sticks while we waited for the rest of the passengers to arrive.

I’m not sure who noticed it first, but someone pointed out that there was something wrong with the pinwheels while we were in the jeep. A pinwheel spun from the front of the jeep would somehow boomerang back to the front. A pinwheel placed on the right seat would be found on the left without anyone spinning it. There would be more pinwheels at the end of the trip than there were when we started, or sometimes there would be less. My friends and I would look at each other, wide-eyed, thinking, “Is there a ghost in here?” No more talk of pop culture. Instead, we would talk about the haunting in hushed whispers, afraid to anger the ghost.

I don’t think anyone truly believed it, though. I didn’t. But now, thinking about my last memory of the service, I’m not quite sure.

The school day just ended, and barely any of my servicemates were in there. The driver was out of sight, so I took the chance to see the front seat for the first time. Little girls weren’t allowed at the front. I set my eyes on all the religious paraphernalia adorning that side of the jeep—a rosary hanging on the rearview mirror, pictures of saints on the dashboard, a small sticker of the Virgin Mary stuck on the windshield. Mother Mary was staring into my eyes when I felt blood gushing from my knee. Did I bruise my knee when I was running with the other kids? (I don’t recall playing.) Did I accidentally graze myself on a sharp piece of shrapnel while sitting? (I don’t remember feeling anything bump against my leg.)

Maybe. Or maybe not. Shortly after that, I told my mother I was going to ride with her again.

Read more: Being independent at 20 before graduating can be tiring

Vieta’s formulas

by Dani Pesayco

Vieta’s formula in mathematics is a formula in finding the numerical coefficients of a polynomial, relating the coefficients as the sum and product of its roots. But years before I learned this term in algebra class, I first heard it from a boy on the school bus nine years ago.

At the crack of dawn, in the peeking light of the sun, with the hum of the engine and soft snores from sleeping busmates, I usually took this time to complete my unfinished mathematics problem sets from the night before.

He, the math genius, just so happened to sit beside me that morning.

“Tulungan na kita?” His words were met with my sighs of frustration and relief as his guidance was most appreciated. “Ah! Kailangan kasi gamitan ‘to ng Vieta’s formula.” Vieta what? I can’t remember much of the problem, but all that remained in my head was Vieta’s formula. He explained to me how it tied in to the problem we were solving. I gave him the most confused look. No matter how much he tried explaining the math to me, I just couldn’t get it.

Then he leaned in towards me so closely—close enough that our heads were almost touching—with an excuse about seeing the equations better. And that’s when I realized where the confusion was coming from.

I felt a jolt of electricity as my hands froze and my breathing quickened and my eyes met his. He looked up at me—I swear, the small space between us filled with the same electricity—and laughed, fumbling over the math until he himself was stumped. Obviously, that did nothing at all to help me understand Vieta’s formula that morning.

It’s been five years since the last bus ride home, six since that pivotal moment, and nine years of keeping this crush and its whole spectrum of feelings in between heartbeats and the folds of numerous diary pages. I figured out Vieta’s formula, it was easy enough after a while. But it’s been nine years and I still couldn’t figure out this spark, that electricity, the very reason why he had to lean into me and why I allowed him into the small of my usually cordoned off comfort zone.

This complex…thing is exactly like math. Just when you thought you’ve got it all figured out, you realize you forgot to turn that negative sign to a positive one or you misplace a variable. But then you find the perfect formula to piece the complexity together and it all just makes sense.

Illustrations by Tyra Monzones

This story is originally published in our 35th issue and has been edited for web. The digital copy of Scout’s 34th issue is accessible here.

Comments