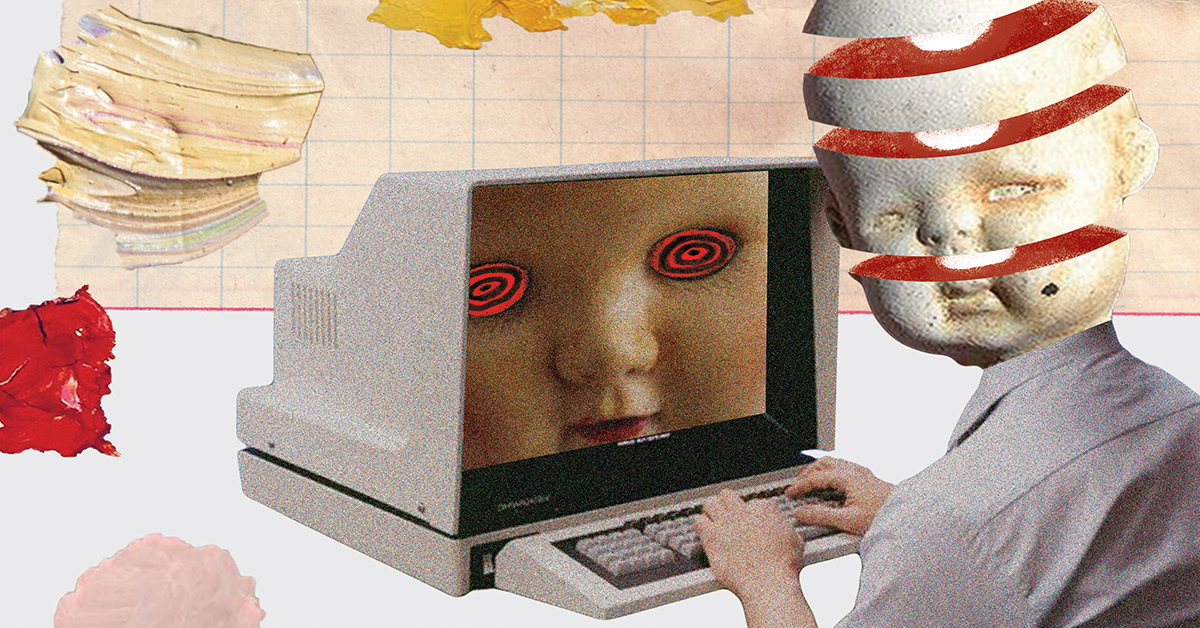

A friend once said that social media has gone from a way to take a break to something you have to take breaks from. The degree of power it wields—to connect, reach out, have our voices heard by people anywhere in the world—also comes with the potential to bring out the worst in us.

By Rissa Coronel

A lot of us have, at some point, been unwitting spectators of personal and public drama. Sometimes we watch with anticipation, or even add fuel to the flame as celebrities and regular people alike are roasted—dragged, ended, canceled—in 140 characters or less.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but that thoughtless comment might leave long-lasting psychological scars. If you believe online shaming is not a big deal because it’s “not real,” think again. In our efforts to defend our side of the argument—especially if it’s someone we don’t like—we forget the human on the other side of the screen.

It really does a number on the self-esteem of those targeted. Mica* experienced it because of a real-life misunderstanding, and says that it definitely took a toll on the self-esteem of those involved: “You’d think you’re only as good as people say you are.”

Sandra* also experienced a crossover from a real-life fight that eventually turned into straight-up online bullying. It ruined her reputation among her social circles, especially when an unknown number claiming to be her repeatedly harassed several people via text. “I didn’t even know half the people who liked the tweets calling me out,” she says about the ordeal. Her depression reached a point where she experienced suicidal urges—her real friends slept at her condo to make sure she didn’t do anything rash.

Slut-shaming will always be offensive and hurtful, no matter the medium. Zoey* (see sidebar) became depressed, suffering from very low self-esteem and trust issues, with “episodes of thinking about why someone would shame [her] for a harmless post.” Kaye* admits to becoming suicidal after reading insults about her appearance. It takes some people a long time to learn how to be comfortable with themselves, and thoughtless words can derail all that progress.

The many messages and threats that university professor Nathania Chua has received initially made her afraid for her safety. “I went on a total lockdown in terms of my physical privacy and location for a while.” She quickly moved past these incidents, especially remembering that most of the accounts were created by social media machineries just to harass her.

Nona* also quickly transcended her experience with online shaming, considering it relatively less severe but still annoying—especially since she was attacked for simply not liking a film. “I’m used to critiquing culture from a political and societal lens, but seeing those people ignore my critique and make fun of my points… You can’t help but get annoyed.”

Janice*, on the other hand, was able to realize from her experience that sexist jokes and gender insensitivity could push someone over the edge: “What I think is just an offhand or meaningless thing could be the thousandth time someone has heard that insult.”

***

The internet has made it impossible to commit mistakes unnoticed. So much more is expected of us in terms of fact-checking, cultural sensitivity, and political correctness. Our real-world misbehaviors might even be secretly recorded, like what happened to “Amalayer Girl” back in 2012, when a video of Paula Jamie Salvosa was recorded screaming “I’m a liar?” at someone else on the LRT had made the rounds a few years ago. (She has since used this incident as a learning opportunity to strengthen her faith and now works full-time for a Christian ministry.)

Janice mentions that people calling you out isn’t always bad. “Realize that they’re coming from a different place than you are, and their thoughts are shaped by experiences. Listen to what they’re trying to tell you.”

Although there are people like Janice who manage to be reflexive while being shamed online, there are more tactful ways to correct someone that don’t involve embarrassing them in front of their whole friends list. Like in real life, you’re likely not going to listen to someone’s points if they come at you with hostility and disrespect. Mica points out, “There are better and more private ways of handling conflict, that won’t involve attacking the person publicly. More often than not, it puts you under a bad light as it reflects your personality.”

This is especially true of those who let their prejudices show in their online comments, like those who slut-shamed Zoey and Kaye. More people are becoming aware of the faults of slut-shaming, but it still happens. Jane*, who witnessed her resulting depression firsthand, adds, “I wish people would let others do whatever makes them feel good if it doesn’t hurt anyone else.”

Nona mostly dealt with online shaming by exercising her right to use Twitter’s mute function. She also advises that “a solid, objective view of the conditions you’re being put in helps, especially if you aren’t doing anything wrong.” If you’re dealing with a serious case of harassment, the report and block buttons have got you. Online harassment is the main reason social media sites have those functions in the first place.

Nathania has a similar view of the trolls in her situation. She sees them as noise that distracts from the messages she wants to convey. “I remember all the people I’m doing it for, the people who [need] someone to speak out on their behalf.” Her advice to those who experience online harassment is to remember who you are as a person, in spite of the insults or lies you may read about yourself. “Do not allow them to make judgments about who you are. These people have only judged you by a series of tweets, or even propaganda spread against you. If you know who you are and what you stand for, the battle will be a bit easier.”

Difficult as it may feel to move out of a headspace where you keep thinking about your online presence, you have every right to take a social media sabbatical when it becomes too much. A few respondents acknowledged the fact that we don’t live on the internet alone. At the end of the day, we are not confined to an online space a la Black Mirror.

Whether your battle is to shed light on sociopolitical issues, comment on new forms of art and media, or practice self-love by posting your outfits, “you have to take your tweets to the street,” as Nathania quips. “Real battles are won offline. It can’t be all social media, all like, share, retweet. Ultimately, your actions have to speak much louder than what a post would say.”

How Online Speech Goes Wrong

Social media makes it easy for people to throw shade, which means it’s easy for harassment to quickly snowball online. The following are real accounts of people’s experiences with online shaming and harassment, as told to the author—some incidents will be kept vague to protect the respondents’ privacy.

Online shaming, bullying, and harassment. Janice* got dragged (and rightfully so, she reflects) for being sexist on Facebook and various forums, while three other respondents mentioned that they were bullied online for “real-life bullying that extended to the internet.”

One-sided discourse. Shaming someone online can be done with the misplaced intention of “educating someone”—which sometimes masks a desire for likes within our social circles, brownie points for wokeness, as writer Nika Dizon explores in an article on Scoutmag.ph. The option for likes and shares can make social media more like an approval machine, more than actual engagement.

Cultural activist Nona al-Raschid’s experience with online shaming happened on Twitter, after she posted a thread explaining why she couldn’t relate to a certain film. “The direct responses I got were positive, [but] I was alerted to people subtweeting me.” Complete strangers mocked her personal opinions, making fun of her argument and the examples used in her thread.

Political propaganda. There are a lot of insensitive and legitimately hateful things floating around on the internet. This is especially seen in the context of our tense political climate here in the Philippines, manifesting online through trolls and fake news. This shapes public opinion with warped versions of the truth, even going so far as to harass those who disagree.

An example of online political harassment would be that endured by Nathania Chua, a university instructor vocal in her criticism of the current administration. In retaliation for her pointed critiques of blogger-turned-government official Mocha Uson, Nathania’s online details were exposed in a post made by political activist Sass Sasot. Nathania recalls that in the post, “Sass fabricated a lot of things about me, about how I work and my institution.” She mentions there was no basis to what Sass said, and both Sass and Mocha have thousands of followers who believe the propaganda peddled against her.

Slut-shaming. Two of the responses had to do with slut-shaming, as Zoey* was called out for posting a photo of herself in a crop top. Kaye*, on the other hand, was insulted for her clothing and looks. Guys, it’s the 21st century, and some people still can’t wrap their minds around the idea that what people wear is none of their business. There’s no harm in someone being proud of their looks and posting an #OOTD; what’s harmful is making assumptions about a woman’s character or sex life based on her clothing.

*names changed to protect privacy.

Illustration by Nika Dizon

Comments