The drug war, extrajudicial killings (EJKs), questionable government priorities and red-tagging. These are only a fraction of the injustices we’ve witnessed, all depicted in two minutes and 30 seconds of pixel animation called “Spoliarium 2K20.”

Chances are, you’ve seen it pop up on your Facebook feed recently. It’s a work of pixel art animation made by multimedia arts student John Clister Santos. After posting the video on his Facebook page Clister.Art, the video has since garnered almost 9,900 reactions and over 10,000 shares as of writing.

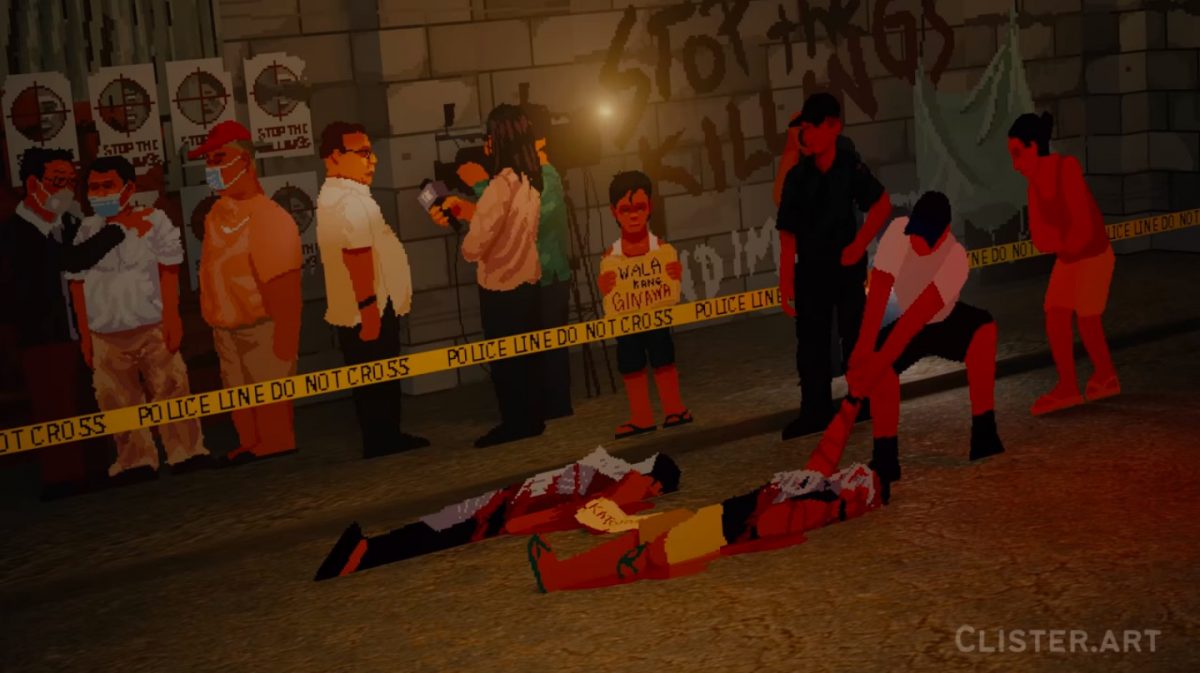

Clister’s “Spoliarium 2K20” blends 2D with 3D elements in a reimagination of Juan Luna’s most notable painting, “The Spoliarium.” Luna’s oil-on-canvas masterpiece takes viewers down the basement of a Roman colosseum, where fallen gladiators are dragged on the pavement as their loved ones weep and onlookers eye the spoils of the battle.

Much like its inspiration, the video opens with a gritty scene, Bullet Dumas’ “Usisa” playing as a man drags a dead body across the gravel. A woman grieves over the lifeless bodies, journalists immortalize the scene in visual documentation and politicians at the side chit-chat as Bullet sings, “Ayaw mong makita / Ang nabigong panata / Ito ang halimbawa / Ng kahayupan nila.”

It’s a scene that feels familiar, perhaps from watching recurring footage of the drug war. Yet it also feels distant, as no words will ever be enough to describe the pain of EJK victims and the families they left behind.

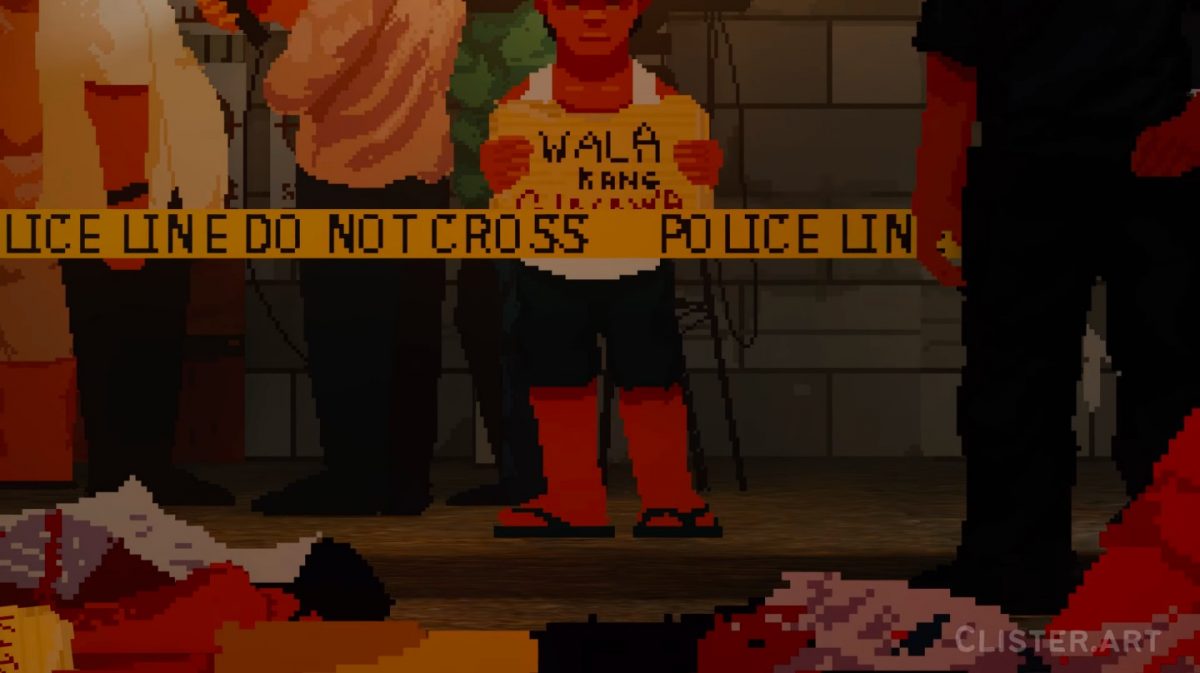

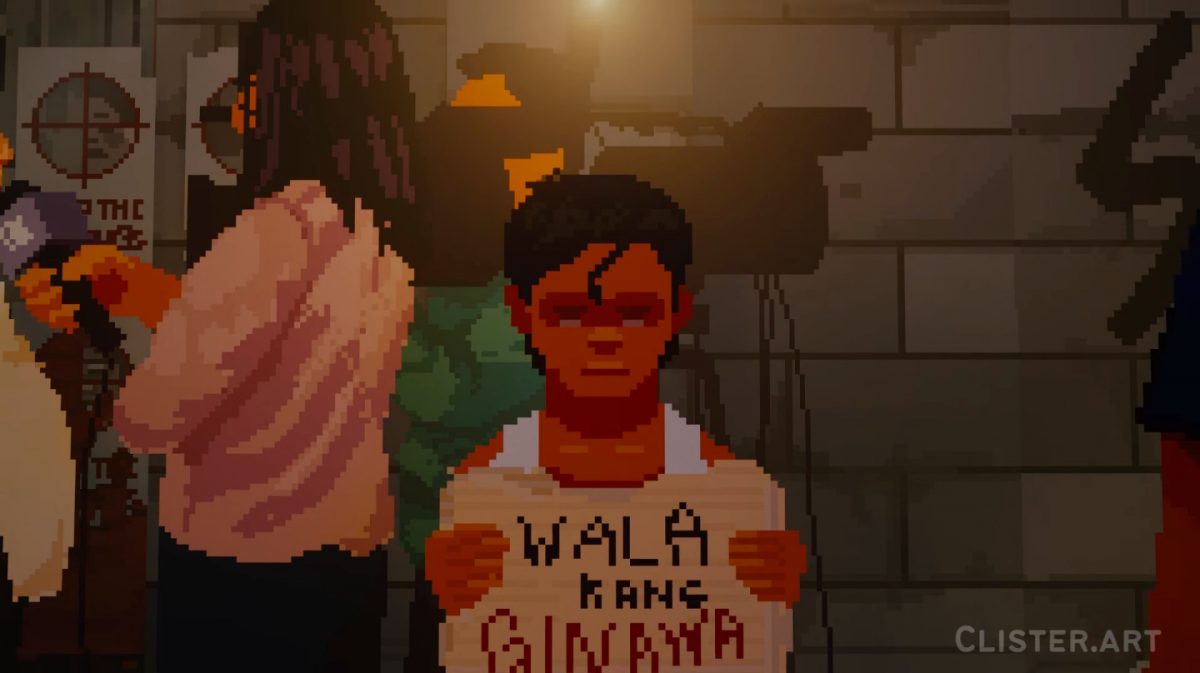

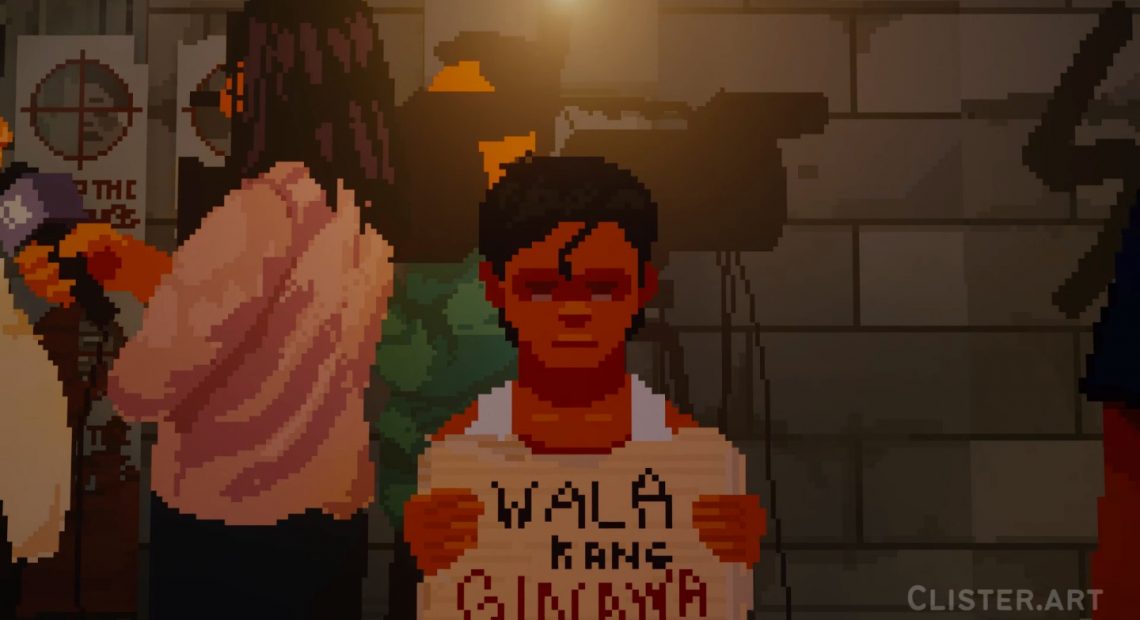

The youth is at the center of it all, torn between witnessing the injustices unfold and doing something to amplify voices, as depicted by the figure holding a placard with the words, “Wala kang ginawa.”

We sat down with Clister to dissect the elements in “Spoliarium 2K20,” as well as talk about experimenting with art media and what artists’ role in activism is.

Watch the video here.

Tell us your creative process behind “Spoliarium 2K20.” What was the vision for it?

Nagkaroon kami ng finals for my art appreciation subject. We were tasked to reimagine any notable local or international art and make our own version na relevant for our age. As an animation student, I’ve been experimenting with many [media] for the past few months since the lockdown, and I came across pixel art. Na-astigan lang ako sa pixel art kasi it’s a great medium. You can create realistic yet abstract pieces at the same time, and nagiging palatable siya sa maraming artists.

Many artists have enriched Filipino art history. Why did you choose Luna’s “The Spoliarium” in particular?

I first saw “The Spoliarium” when I went to the National Museum last year. It stuck in my head. Like, you first see it, it makes you feel na nasa harap ka talaga ng mga gladiators sa Colosseum. Ramdam mo ’yung movement, and you feel haunted by the bloodbath in front of you. And I’ve always wanted to recreate “The Spoliarium” with a very modern take, and I saw na this was the perfect time. ’Di ko in-e-expect na magagawa ko, nagkataon lang.

“I see that the EJK issue is being forgotten and it needs to be amplified again.”

There are a lot of references in the animation. What was your thought process behind selecting these references?

Before starting the project, we were trained to create storyboards and moodboards before creating this. I carefully selected elements that I wanted to preserve from the original painting, but I added some new elements pa rin.

Doon sa original painting ni Luna, there were three key elements: the politicians on the left, the gladiators in the middle and the woman on the right side. Those three elements… I kept [them] pero ginawa ko siyang modern. Like the politicians, the current and most powerful ones in the government. Tapos ’yung sa middle, instead of gladiators, I made them into the victims of the drug war, the EJK. On the right side, sa original painting, ’yung woman dun, nag-mo-mourn siya doon sa mga bodies ng gladiators pero this time, she’s mourning for her child who’s a victim of EJK.

What about the person holding the placard?

Ah, yes, that’s an additional element. Sa original painting, the one in the middle is a guy pointing sa malayo. Dito sa bago ko, I wanted the focus to be on the youth, kasi I see the youth as being powerful in today’s political landscape, [as shown] with the placard that says “Wala kang ginawa.”

I tend to choose the youth as a subject. Like, I see myself in it. Dati, ’di ako ganoon ka-politically open sa mga topics. But now, nakikita ko ’yung posisyon at privilege na I have to amplify these kinds of issues. Nilalagay ko ’yung sarili ko sa posisyon ng mga subjects ko, like I see myself in that kid.

A lot of notable pieces of art are, in themselves, forms of activism or artvism, which marginalized people or undermined sectors take up space through art. Would you consider your work “Spoliarium 2K20” as a work of artivism?

Yes, of course. It was actually one of my first political animations. I was actually hesitating to post this, lalo na’t maingay ’yung red-tagging ngayon. Pero I see that the EJK issue is being forgotten and it needs to be amplified again. Tsaka giving respect na rin kay Juan Luna, as isa siya sa key political activists during the Philippine Revolution. Nakikita ko ’yung Spoliarium 2K20 as a mirror nung original painting, thematically and visually.

“I first saw ‘The Spoliarium’ when I went to the National Museum last year. It stuck in my head. Ramdam mo ’yung movement, and you feel haunted by the bloodbath in front of you.”

You mentioned that you were hesitant to post your artwork, which actually even gained a lot of attention when you did. Why do you think your fellow artists shouldn’t be complacent with what’s happening in society?

I think as artists, we could do something about this. I see na ’yung mga recent animations ko, ’yung the positive, nostalgic side of Filipino culture… nakikita ko na shineshare siya ng mga tao. Nakakita ako ng potential na it could actually send a message na, nakakarelate ’yung mga tao sa dati. Baka dito sa bago kong art, it could be powerful but also disturb them. It could urge them to speak [up about] these issues.

Art is a powerful tool, even more powerful when used to call for social change. What do you hope viewers would take away from watching the animation?

I want people to see the potential of pixel art and animation itself, and how they can be utilized to send powerful messages. As they say nga ’di ba, art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable. I hope that my version of Luna’s “The Spoliarium” will be able to recreate the impact it had when it was first shown to the public. I want viewers to be reminded of the horrors of the Philippine drug war.

“Nakikita ko ’yung posisyon at privilege na I have to amplify these kinds of issues.”

’Di ko siya in-e-expect talaga. Kasi ’di ba originally ang nag-implement ng Tokhang is si [Senator] Bato, pero ang nalagay ko na doon is si Sinas and nagkataon na siya ngayon yung in-appoint. Grabe ’yung timing talaga.

How do you see your role as an artist?

’Yung works namin [as artists] will forever exist on the internet, and will be seen by thousands of other people in the coming years. I hope that maka-inspire pa kami ng maraming tao to be artists and speak up against injustices in whatever form they can. As one of my previous teachers said, let there be art to every injustice.

Follow Clister on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

This story is part of our #SeenOnScout series, which puts the spotlight on young creatives and their body of work. Clister and many other creatives shared their work at our own community hub at Scout Family and Friends. Join the Scout Family & Friends Facebook group right here, and share your work with us in the group or through using #SeenOnScout on Twitter and Instagram.

Read more:

This art student transformed canned goods into protest statements

Electromilk’s “quiet, marble-y images” always have something to say

This digital artist sees Manila through bitmaps and pixels

Stills from “Spoliarium 2K20”

Comments