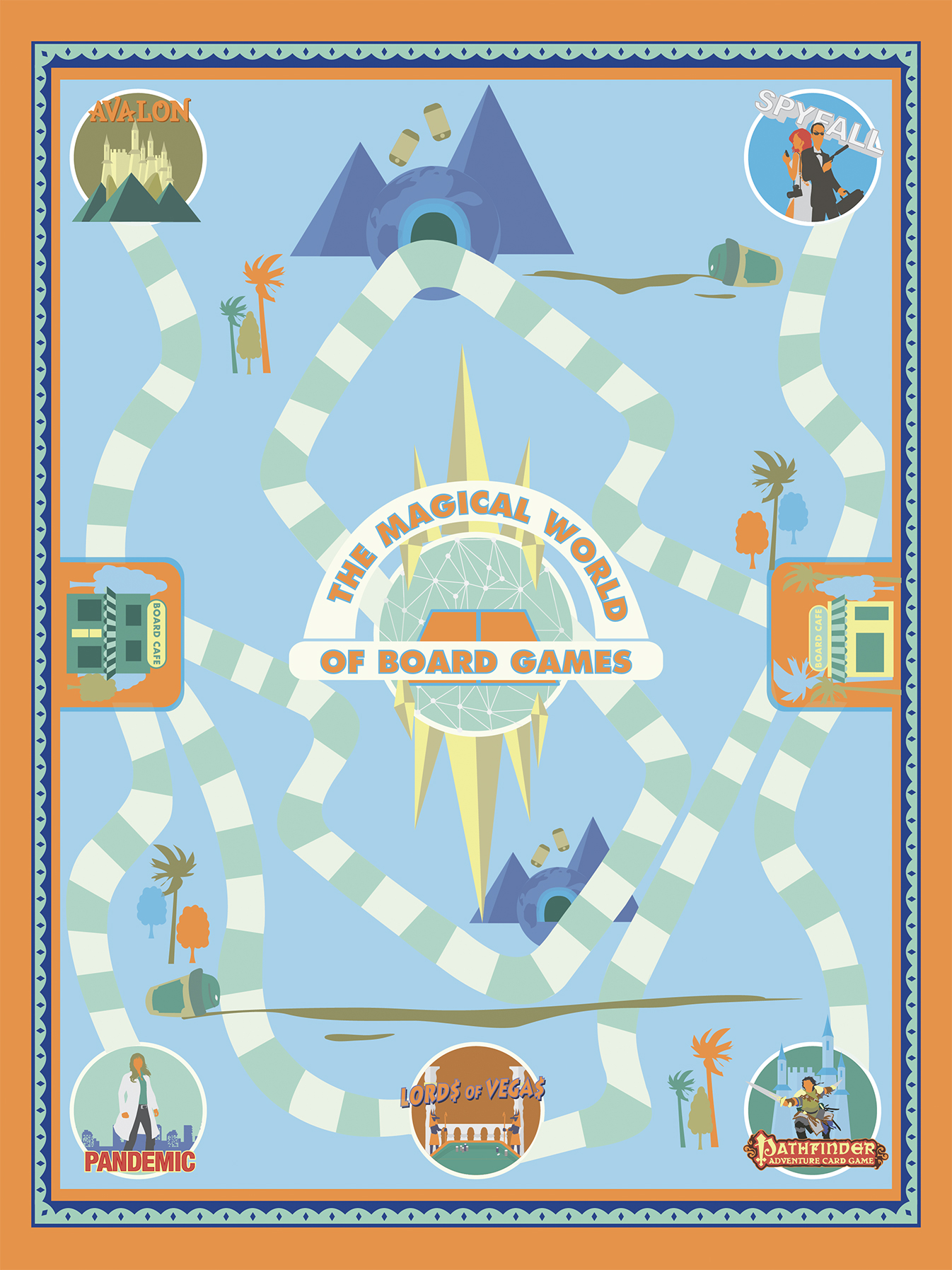

By Franco Antonio Regalado. Illustration by Maureen Gonzales

I am playing The Resistance: Avalon, a game about rooting out hidden traitor players from King Arthur’s forces. I am playing Merlin, who knows who the traitors are, but is being sought after by them as well.

The player to my right picks a team of three. There is one traitor in there. I want to call him out, but to do so at this point, so close to the start of the game and with so little information, would place too much attention on me, allowing them to guess my identity too easily.

Grudgingly, but trying to not let it show on my face, I join in the approval for the team.

If the steadily increasing number of board game cafés, board game restaurants, and people looking for copies of The Resistance are any indication, board gaming is more popular than ever.

“Board games, like Monopoly or Snakes and Ladders or Scrabble or chess? Isn’t that stuff for, like, bored kids and old people?” is a question I hear often, when I tell people that I play board games, the answer to which is that those four titles are just a shard at the tip of this wonderful, wonderful iceberg that is the board gaming scene of today. Nowadays, board games are as varied as people, requiring you to do things ranging from bidding at auction to declaring attacks against opposing forces to detecting elaborate bluffs and everything in between.

Hobby board gaming may look daunting to the uninitiated based on numbers alone: tens of thousands of choices, all varied in how they play and play out; five-minute rounds of rolling a few dice and deciding whether to roll again or not on one end, sprawling maps with fluctuating in-game economies and logistics networks which take half a day to complete on the other. And let’s not forget the cornucopia of mechanics, requiring everything from reading facial cues to risk management to auction timing, possibly even a little to a lot of luck.

___

I am playing Pandemic, a game about a team of specialists trying to contain and cure viral outbreaks all over the world. My role, the Medic, allows me to remove more of a disease, represented by small plastic cubes, from the board, keeping it suppressed for longer. On a hunch, I move into Ho Chi Minh and Manila, two of the most infected cities in the Southeast Asian region, and proceed to clean them up.

The next infection strikes… Manila.

I breathe a sigh of relief, knowing that my work means that the virus doesn’t spread to any neighboring cities that turn.

So what brought this all about?

The popular theory is that, nowadays, people are beginning to discover the limitations of technology games, and rediscovering the pleasures of returning to analog. With board games, people can explore and indulge in the nuances of face-to-face communication.

Board games provide a necessarily visceral level of interaction: details such as tone of voice, expressions, even one’s ability to hold a straight face as you make a move, or try to figure out another’s moves, are always lost in the written medium. This, after all, is communication and interaction in its purest form: both blatant and subtle, loaded with meaning beyond words.

This, perhaps, is why game genres such as social deduction and dexterity are among the easiest to teach to new gamers: social interaction, from white lies to suspicion and deduction, is human nature, in a way that long-term strategy, a grasp of mathematical probabilities, an appreciation of thematic elements, and other factors may not necessarily be within one’s aptitude, gamer or not. Same goes with dexterity: that feeling of stacking that one piece perfectly on top of another—Jenga is the most popular example, but I’d recommend Rhino Hero and my personal favorite, Animal Upon Animal, instead—or flicking that wooden disc so that it hits an opponent’s piece at just the right angle (see: Catacombs, Flick ‘Em Up!) brings out such a primal sense of fulfillment that one can’t help but acknowledge such small triumphs with a solid high-five.

Truth be told, even more mathematical endeavors, including Power Grid, Imperial 2030, and Agricola, still make use of the interpersonal magic of board gaming, eschewing spectacle and theme for often wide, wide stretches of imagination, suspension—even outright denial—of disbelief draped over competitive probability and risk management exercises, not to mention the simple tactile pleasure of wood, plastic, cardboard, and paper.

____

I am playing Pathfinder Adventure Card Game: Rise of the Runelords, a game about fantasy adventurers hunting down monsters to complete quests. I am Sajan, a monk who specializes in boosting his and others’ abilities by casting blessings, a special spell class that makes it easier to overcome different sorts of challenges.

On my turn, I encounter the scenario boss, an acid-spewing dragon by the name of Black Fang. I attack, adding a blessing bonus to roll 3d10 instead of 1d6. I need 12 to win. The rolls come up 8, 1, 1, just short to kill the dragon. It retaliates, forcing me to discard cards, and escapes, eating away at the number of turns we have left before we lose.

Well, crap.

From storytelling to risk and resource management to grand strategic moves, board gaming has come a long way from the Monopolies and Snakes and Ladders-es of yore in terms of game mechanics.

Does a game where you hold a hand of cards facing away from you sound interesting? Check out the slow-burning Hanabi and the frantic Bomb Squad. Would you rather toss dice than roll them? There’s instant-classic Tumblin’ Dice and the hilarious Dungeon Fighter for that. Fancy bluffing your way out of an accusation? Games such as Coup, The Resistance, Spyfall, Mascarade, Werewolf, Mafia de Cuba, among nearly countless others in the social deduction genre all involve some form of this. Want to just sit back and participate in some shared storytelling? Once Upon a Time: The Storytelling Card Game and Tales of the Arabian Nights put a little game into fairy and folk tales, respectively, to the end that winning, that traditional way of enjoying a board game, takes a back seat to creating a memorable narrative.

___

I am playing Lords of Vegas, a game where the players are developers trying to turn the Las Vegas strip into the gambling capital it is today. I am short a million dollars to build a new casino, so I gamble at a neighboring casino, hoping to win enough to give me an edge over the others. I bet two million, and roll two dice: a combined result of 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, or 12 means I win, with the 2 or 12 forcing the house to pay me double my bet.

The dice come up 2 and 1. I use my cash, along with my winnings, to build a new casino along the edge of the strip, and pass the turn with only one million, but a potentially lucrative chain of space-themed casinos.

Life is good, for the time being.

Fortunately, it seems people are beginning to catch on locally as well. At least five gaming cafés opened in Metro Manila in 2015. Several places have evolved past their origins as Magic: The Gathering stores and tournament venues, branching out into hearty meals, gourmet coffee, trained game coaches adept at giving game suggestions and teaching game rules, and steadily growing library-slash-collections for visitors to peruse.

Game groups have sprung forward as well. Almost every city in the metro has a local game group or two, with regular meet-up sessions, coordinated either through text or through Facebook, for their gaming fix. The inherently social and physical nature of board gaming as a hobby coaxes this sort of interaction; the solo genre of board gaming—yes, it exists—is a small niche, with games almost always requiring player counts of two or more to pull off their magic.

The best part of all this is that there are now so many entry points for anyone who wants to give board gaming a try. Hitting up a nearby board game café and joining a board game group online are the usual options, but events such as gaming meets, and game store appearances in geek conventions, and the like, are all awesome opportunities to get into this wonderfully social hobby, which Quintin Smith, one of my favorite board game reviewers, describes as one of the best ways to sit down with people and talk without everybody needing alcohol.

I am playing Spyfall, a game where one player plays a spy, and tries to guess a secret location known to all players, while the other players try to guess who among them is the spy. Our secret location for the round is “the beach.”

I look to my right, and ask my friend, “What do you wear to this place?”

He smiles, and answers, “Rubber shoes, of course!”

I notice his hands fidgeting.

Comments