SCOUT Friday Picks is our dedicated column on music, with a focus on familiar faces and new, young voices. For recommendations on who you want us to feature next, tag us on Twitter and Instagram at @scoutmagph

[Trigger warning: This article mentions mental health struggles and suicide.]

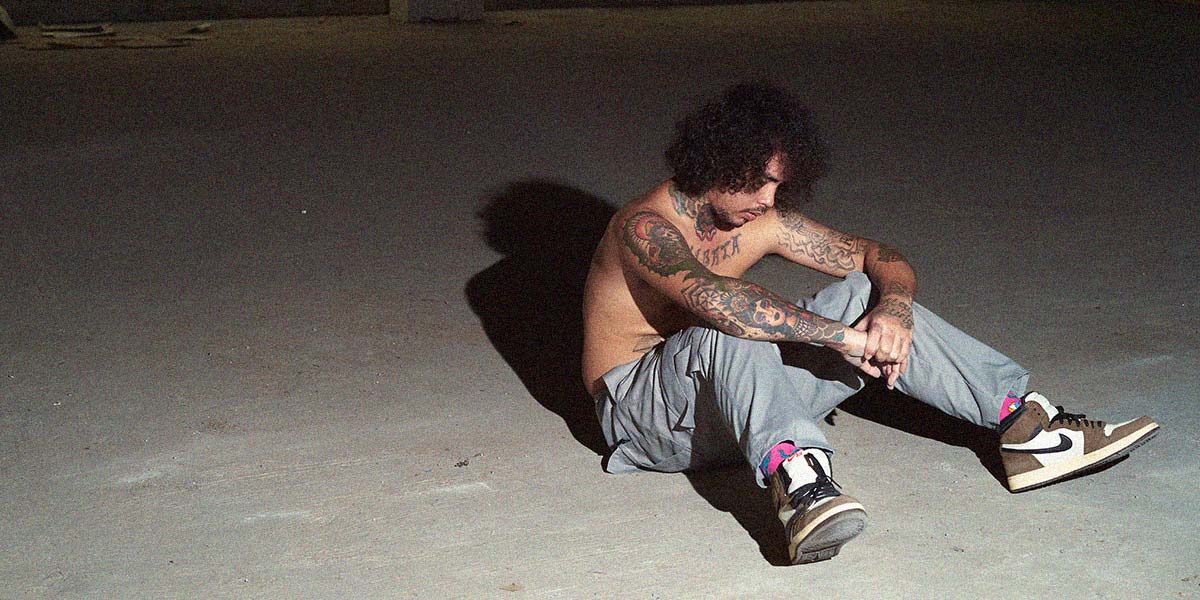

If you studied in the same high school as Jerald Mallari, you would probably have spotted his name written on the sign-up sheet for the yearly Battle of the Bands. But it’s not the springboard to success we might imagine: No one wanted him in the first place.

“Ayaw nila ako isali kasi uso nu’n mga punk. Paramore. Ta’s ’matic na kaagad, panalo na kapag ‘Ang Buhay Ko’ (‘yung pinerform),” he quips. “Sumasali na akong banda; wala lang tumatanggap sa ’kin eh. Kaya sabi ko, ako gagawa ng banda. Ako mag-isa magiging banda.”

(They didn’t want me to join because punk was the thing that time. Paramore. You’d automatically win if you performed “Ang Buhay Ko.” I tried joining bands; no one would accept me. So I told myself, I’ll make my own band. I’ll do it on my own.)

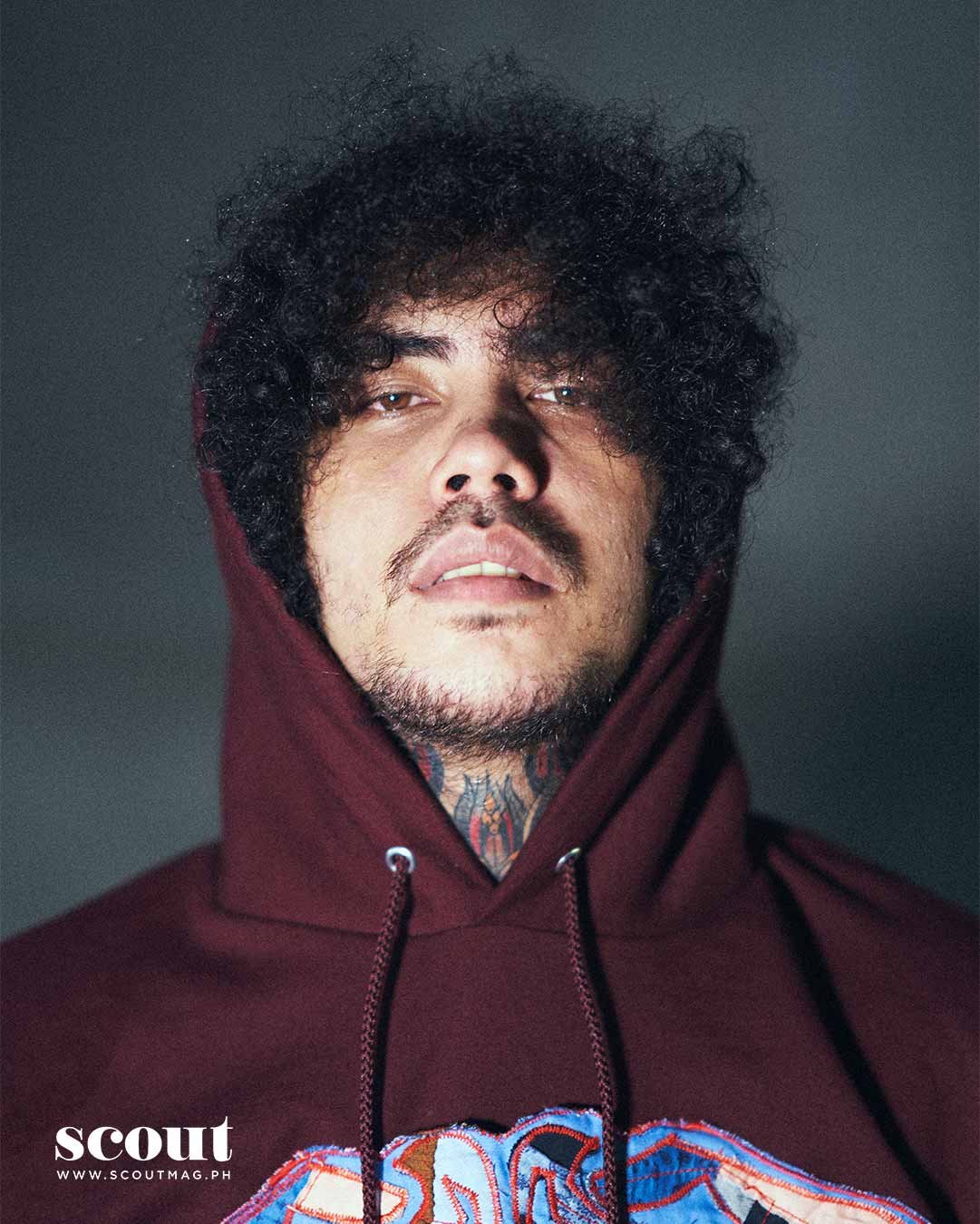

“Mental Instruments” Patchwork Pullover Hoodie from Fortune W.W.D

It wasn’t just rappers who lacked a place in these programs. For the young hip-hop enthusiast, he struggled to find a domain in Bataan, his own home. “’Pag hip-hop ka dun, tatawanan ka pa. Ang gusto nila, mga ‘Pusong Bato’ type beat. Mga pang-karaoke. ’Yan ’yung mga standard,” he recounts. “Eh nung panahon na ’yun, parang si Gloc 9 lang ’yung ganun.”

(If you’re a hip-hop artist [in Bataan], you’d be laughed at. They preferred a “Pusong Bato” type beat. Karaoke songs. That’s the standard. At the time, only Gloc 9 [was the image of hip-hop].)

Hurdles in the hip-hop lane

Jerald’s first encounters with music might be filled with the usual Top 10 songs on the radio, but he dreamed of pursuing hip-hop the moment his understanding of it deepened in high school, the era of burned CDs. “Siyempre medyo nauuso na ’yung internet nu’n eh. Sa computer shop, magre-rent ka. Ta’s ayun, du’n ko na-discover ’yung beatboxing, ’yung hip-hop, sina 50 Cent. Doon ko na-realize na gusto ko ng hip-hop pala,” he narrates. “Nag-aral akong mag-produce ng beat, paano mag-mix ng track.”

(Of course the internet was becoming more popular at the time. You’d rent a computer at the computer shop. That’s where I discovered beatboxing, hip-hop, and artists like 50 Cent. That’s where I realized I like hip-hop after all. I studied how to produce beats and mix tracks.)

However, his family wasn’t as thrilled. “’Di nila tanggap ’yun. Pati nga nanay ko eh,” he chuckles. In 2018, he knew he had to make a big move in order to grow. “Pinapalayas na ako sa bahay namin. ‘Rap ka nang rap, kanta nang kanta, magtrabaho ka.’ Kaya narindi ako, umalis ako ng bahay. Tapos nangupahan ako ng sarili kong bahay,” he says. “Kahit ’yung mga kamag-anak ko, mga relatives ko, [ang sinasabi], ‘Anong ginagawa ni Jerald?’”

(They weren’t open to it. Even my mom. She wanted me out of the house. ‘All you do is rap and sing. Get a job.’ I got irritated and left our home. I rented my own place. Even my relatives would wonder, “What’s Jerald doing?”)

Growing up in a broken family with only his mom raising him, he recalls how “shitty” life played out back then. “Wala naman akong laruan eh, kasi ’di kami mayaman. Walang gustong makipaglaro sa ’yo. Kasi nga fucked up ka.”

(I didn’t have toys because we weren’t rich. No one would want to play with you because you’re fucked up.)

Despite his personal struggles, friendships always found a way into Jerald’s space. His whole body is almost blanketed in tattoos designed by friends. One specific design on his chest spells out “Alibata,” which takes a page from him being the youngest in a group (“bata”) and his boxing skirmishes as a kid (Muhammad Ali).

And in a place that’s difficult to present your identity as a rapper, friends also became his first audience. “Lahat kaming magka-tropa, nagra-rap kami. Ta’s may tropa ako na may studio. Record-record lang talaga. Upload lang sa YouTube. Basta alam namin masaya kami sa ginagawa namin. ’Di pa namin na-re-realize na pwede naming gawing hanapbuhay ’to,” he says. “Nagsimula kami 2012 eh. Nung time na ’yun, ’yung rap, sobrang clean rap pa, ’yung mga emcee style.”

(All of my friends and I rapped. We had a friend who had a studio. We’d record and upload stuff on YouTube. We knew we were happy with our work. We didn’t realize we could make a living out of it. We started in 2012. At the time, clean rap was popular, the emcee style.)

In fact, Jerald’s stage moniker, JRLDM (pronounced Jerald Damn), traces its origins to this supportive collective. “Kadalasan sa mga sample ng kanta, pagkatapos nilang mapakinggan, [sasabihin nila], ‘Sheesh,’ ‘God damn!’, ‘Jerald, tangina!’”

(Usually after my friends listen to my samples, they’d say, “Sheesh,” “God damn!”, “Fuck, Jerald!”)

Waffle Patch-Panel Bowling Shirt from Fortune W.W.D

The surprise of “Look MOM I’m Flying”

He didn’t always have time to focus on music, though. As he needed to pay the bills, JRLDM had to grind in a factory, a job he had to take when he was 16. But when things didn’t pan out, he figured it was time to find opportunities abroad. His four-track EP from 2020, “Look MOM I’m Flying,” was supposed to close that chapter of his life.

But listeners who found respite in it helped cancel his plan.

For one, the standout track “Patiwakal” (Suicide) raked in not only compliments, but also gratitude from different people. In a murky atmosphere, JRDLM raps introspectively, “Saan ka dadalhin ng hawak mong baril / Baka sakali lang / ’Pag kinalabit ay baka marinig / Baka mas mabuti pa / Siguro ang lahat ay may sagot na sa mga katanungan kapag dedo ka na,” ending with a hauntingly repetitive, “La la la la.”

In the music video uploaded on underground music channel Local, which now has 4.2 million views as of writing, JRLDM takes a no-holds-barred exposition on hopelessness and self-harm. “Doon ko na nilabas lahat (I let it all out there),” JRLDM tells us.

The impact of this song’s rawness must have had a ripple effect. When you go through the MV’s comments section, you see folks opening up about their problems, especially those who have mental health concerns. However, JRLDM also confesses that he gets worried reading certain anecdotes.

He recounts someone claiming that a friend played the song before taking their own life. “Doon ako natakot eh (That’s when I got scared),” he says, noting it wasn’t the message he intended to have.

JRLDM manages to unpack struggles piece by piece. This is further reflected in his 2022 debut album “Mood Swing,” which consists of collaborations with Loonie, jikamarie, and even Gloc 9, a full-circle moment. The record explores harsh themes from self-destruction (“Lason”) to misery (“Lagi Na Lang”).

Shirt from Team Manila

People now go to his discography to feel validated, accepted, and understood. It would only be expected to feel some kind of self-consciousness, given the heavily intimate treatment towards his work, which is nothing short of vulnerable. But this artist begs to differ.

“Hindi ako naco-conscious na alam nila ’yung ganitong side ko. Proud pa nga ako eh; ikaw, kaya mo bang sabihin ’yung ganung side mo? Kasi ’yung mga tao kadalasan, kaya ayaw mag-open up kasi tingin nila ’pag nag-open up sila, mahina sila. Tsaka magte-take advantage sa kanila ’yung tao,” he explains.

(I don’t get conscious anymore that they know this side of me. I’m even proud because not everyone can do that. People usually hold back in opening up because of the fear of being seen as weak and of being taken advantage of.)

“Mental Instruments” Patchwork Pullover Hoodie from Fortune W.W.D

A new approach to music

Now, the 27-year-old JRLDM has his own family. He has found support in his girlfriend, especially when he was jobless. And in a sea of grungy snaps and promotional shoots on his Instagram feed, JRLDM’s one-year-old daughter Red takes over her dad’s social media persona, with captions ranging from wink emojis to “hahahas.”

“Hindi ka na pwedeng malungkot eh. Sadboi na daddy. Sadboi na father,” he quips, making everyone in the interview room laugh. “’Pag nakikita mo ’yung baby mo, ’yung makulit na, ’yung palangiti na, kahit masama ’yung araw mo, wala kang magagawa eh. Ngingiti ka rin eh. Ewan ko, may anak na ba kayo?” Laughter erupts again.

(You can’t be sad anymore, like a sadboi daddy. When I see my baby being playful and smiling, even if I have a bad day, I can’t do anything. You can’t help but smile. I don’t know, do any of you have kids already?)

With this, he admits that he’d like to make music in a “smarter” way. In “Pansamantala,” he confessed that he had struggles finishing because of his actual mood and vibe not matching what was needed for the song. So he had to be in that zone again.

In his newest track “Biktima,” he made sure he just let his emotions flow more. “Kaya ko pa naman gumawa nung heavy vibes na hindi ko pinipilit ’yung sarili ko. [Tulad sa] ‘Biktima,’ heavy vibe pa rin siya. Pero chill ’yung dating. Sa mas matalino kong paraan at proseso ko ginawa. Kumbaga hindi mo na kailangan pilitin ’yung sarili mo. Pero nandu’n ka pa rin sa bigat mo. Pero hindi hassle ’yung proseso ng paggawa,” he adds, proving he has always taken charge of his music.

(I can still create heavy vibes without forcing myself. Like in “Biktima,” it it’s heavy vibes but more chill. So I’m smarter with the way and process of making it. I don’t have to force myself. The weight is still there, but the process is not a hassle.)

Defying expectations

When it comes to his future, JRLDM refuses to plan ahead. “Ayokong mag-assume eh. Masasaktan lang ako. Kaya tingnan natin,” he says. (I don’t want to assume. I’ll just get hurt. So let’s see.)

What he is sure of is that he knows his craft, is a hard worker, and is surrounded by the right people. And the future of hip-hop is looking up: He adds that it is now more recognized in Bataan, with factory speakers blasting tracks from the genre.

JRLDM has proven his control over his craft through the years despite disapproval that came in different faces and places. He has always been defying expectations to express himself. After all, why wouldn’t he fight for something as big as his life? “Buti may music, kasi kung wala, baka wala na talaga ako. Parang ’yun talaga ’yung naging kakampi ko,” he says.

(Good thing there’s music. If not, maybe I wouldn’t be here anymore. It really has been there for me.)

The Department of Health (DOH) reminds the public, especially those who may have mental health issues, that they can contact the DOH’s 24/7 Hopeline to either help them unburden their emotional baggage or to seek professional help. Hopeline can be reached via hotlines 804-HOPE (4673); 0917-558-HOPE (4673); or 2919 (toll-free number for Globe and TM subscribers).

Produced by Jelou Galang and Lex Celera

Photography by Neal Alday

Story by Jelou Galang

Creative direction by Yel Sayo and Nimu Muallam

Clothes from Fortune W.W.D. and Team Manila