Worlds within worlds within worlds. That’s what we have currently in this virtual reality-inclined climate we have today. Remember those old 3D games that gave us a virtual tour of say, the Great Pyramids, or an old castle out in Europe? It felt like we were there. Today, we can readily immerse ourselves in different universes more deeply than ever before.

There’s this website called MapCrunch that makes a game out of Google Street View and Google Maps by taking you to a random location around the world with the goal of finding an airport to “go home.” The rules are simple: you can only navigate through what is given to you—no markers on where you are, no precedent for where you’ll end up.

The whole experience feels like backpacking across a foreign country. Like a blank slate walking across the frontiers of unknown horizons. But the game has its limits. Everything is rendered in 2D, and in frozen perspectives of only one panel.

We tasked four budding writers to play MapCrunch and write about what they make out of their experience, and much like the game itself they had free rein for what they would write about. The resulting pieces ponder the tech-inclined future of travel, the necessities and limits of the game, and the feeling of going to certain places without actually being there.

things remembered while away for two weeks

By Juno Reyes

Illustrations by Aaron Silao

The engine whirs its sympathy in descent: it worries me that going home worries me. After all is this not all the same: departure and return both having been decided upon a whim.

Just choose a spot and book it, words still fresh in memory. Do not think.

Just go: as if to keep one’s mind busy long enough to leave would be enough to disentangle oneself from the intertwining streets that bore witness to growing-up together.

Before you know it, you’ll be on your way back, fresh as ever.

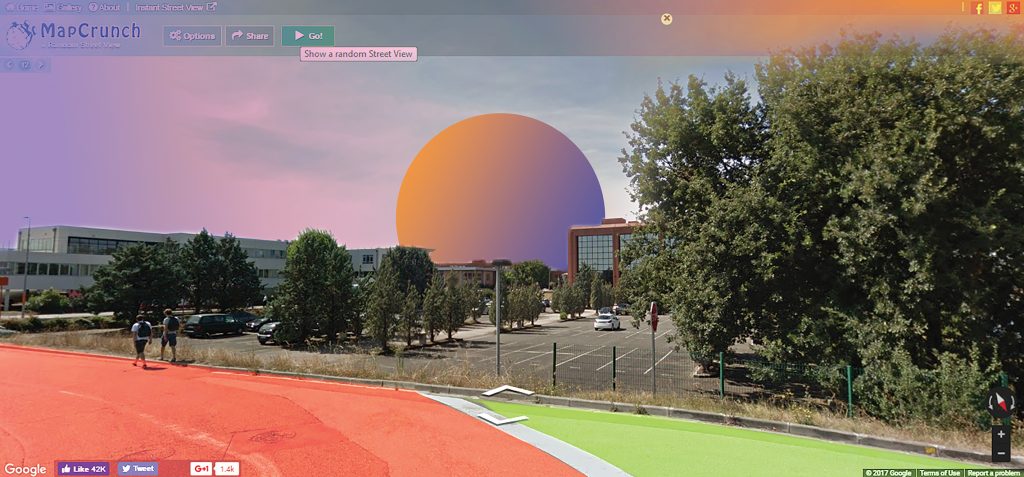

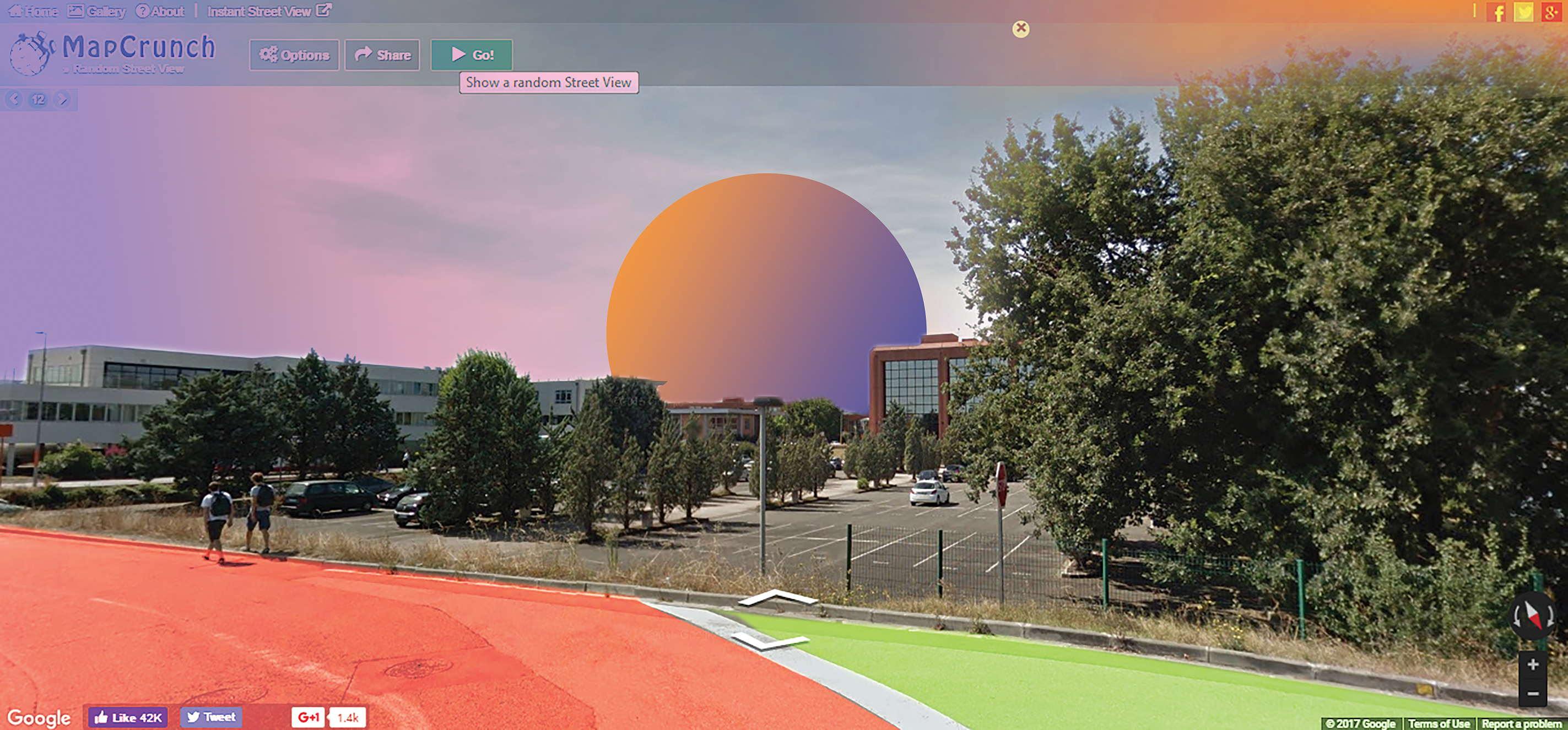

(fig a)

They say a city shrinks when you’re trying to avoid someone. What they failed to mention: the skyline never disappears no matter how much distance you put between yourself and the horizon of the familiar. it only obscures.

At first: I guess I’ll stay in (fig. a) for a year or two, get back to writing, maybe work on my graduate degree to distract myself.

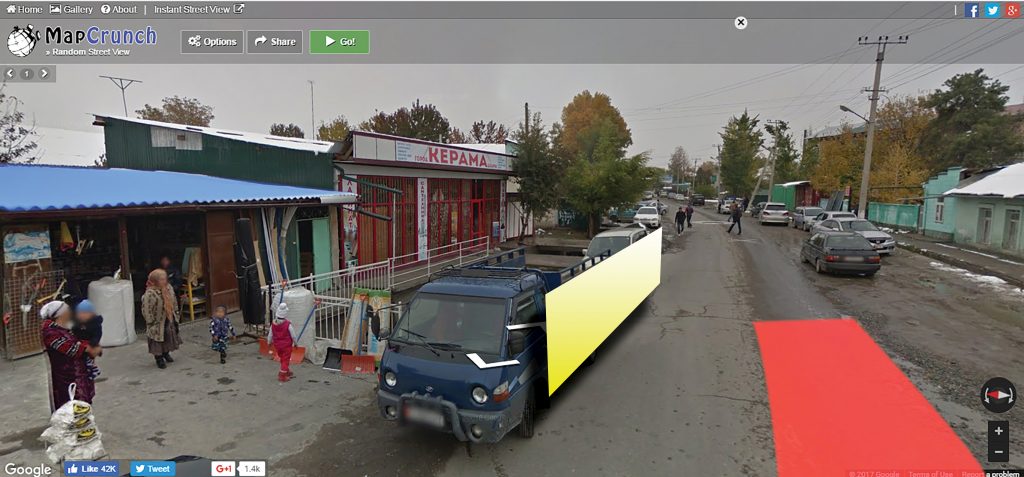

Less than a week later: perhaps it would be better to settle in a small town, like (fig. b),

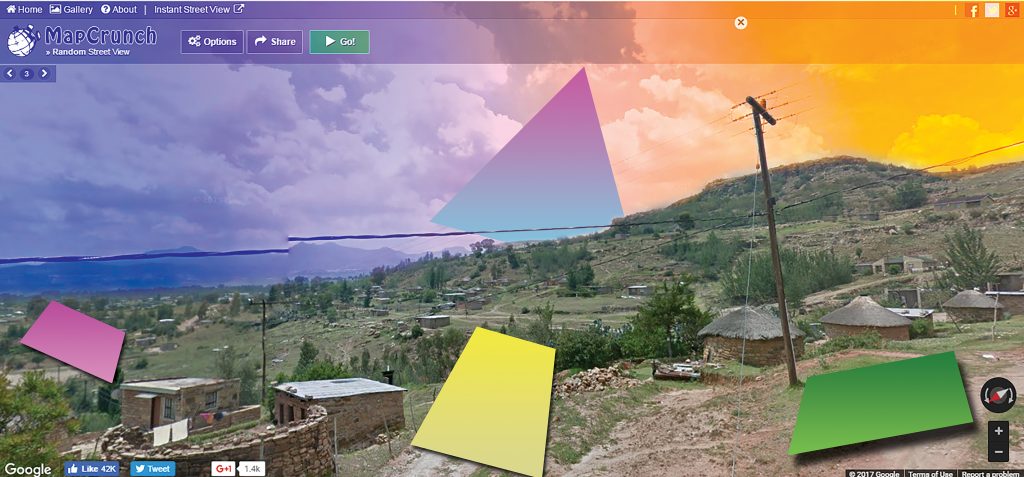

Before one even has the chance to go through all the clothes he has packed: perhaps I shall stay on the road (fig. c). Like a pilgrim. Perhaps I will find my Cid.

But eventually, the restlessness catches up to you, lingers to your clothes like the stench of urban smoke. A familiar weight falls on your shoulder and sits there until you shrug it off motioning your head to look back, where all you see it that all is new is behind you.

(fig. b)

Routines are underrated. I do not know why I am coming back so soon.

This far away, Manila at night looks the exact same way I left it, houses huddled in vigil as if having gone straight to praying for my safe return passage after seeing me off barely two weeks ago. But it isn’t. It is precisely this: two weeks removed from the last time I felt it on the sole of my shoe.

They say a breath of fresh air always helps, that the world unfolds as you make your way out from home. Again, details they neglect: that it collapses back into itself the moment you hop on that rickety caravan on your way back.

The reverse cannot be held to be true: Manila remains even as I venture away from it. Original memory is mapped is later returned to, cartography being precisely the prolepsis of consultation. But it is also its demise: only I remember what I am going home to, never I am going home to what I remember.

(fig. c)

Before heading back to the airport in the city next to (fig. c), I left all my things behind in the hostel where I barely stayed in anticipation of Manila. Or, I did not want to have to take a cab back home. Even then, I already knew, I would have taken a cab anyway. But isn’t this why I had to go away in the first place? This much is clear. I am not coming home to you. Even clearer – I am coming home to someone who isn’t you.

This piece was originally published in our March-April 2017 issue and has been edited for web. View the full issue online here. For physical copies, our delivery locations are listed here.

Comments