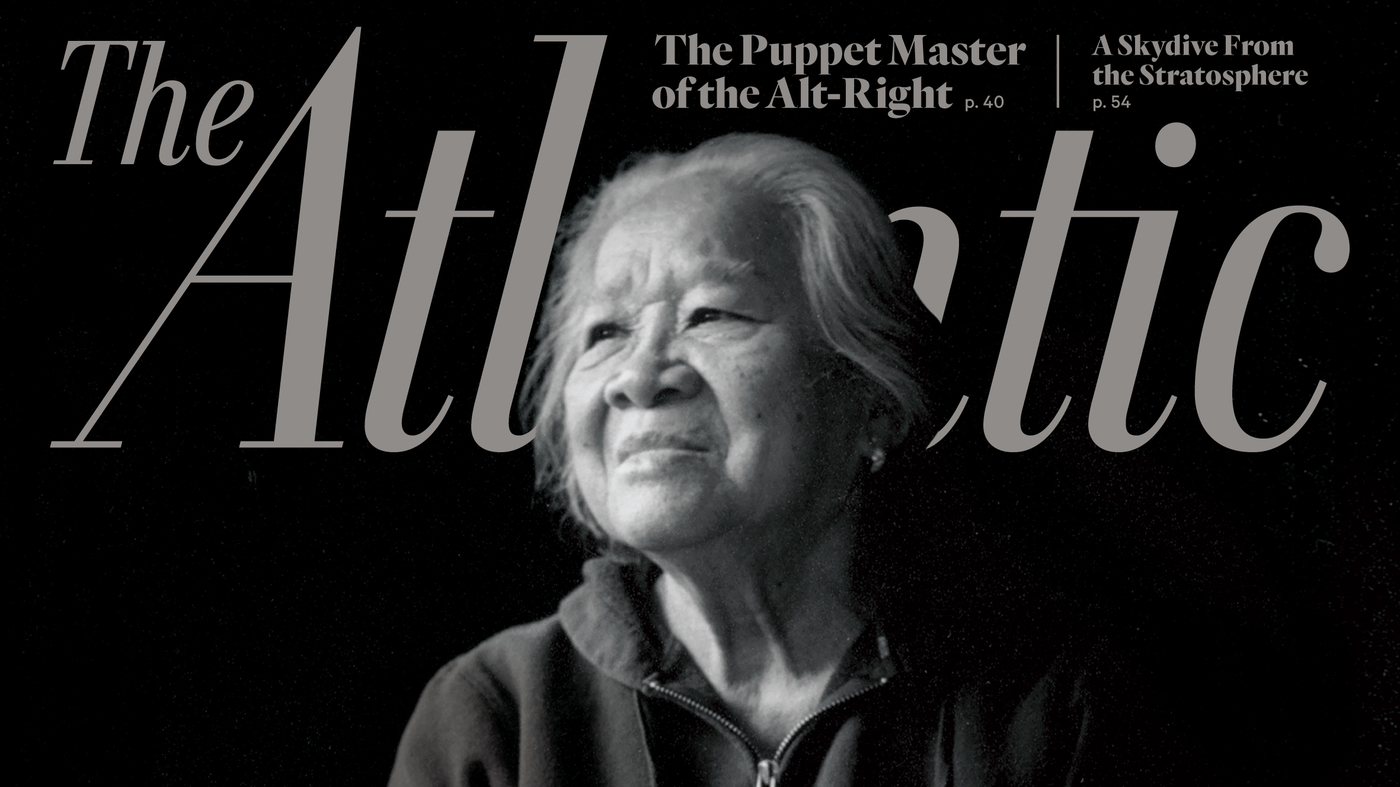

It’s been an evening since The Atlantic dropped Alex Tizon’s personal longform essay “My Family’s Slave,” which went viral because of Lola’s—the Tizons’ domestic helper and, well, slave—situation. If you haven’t read it yet, you need to read it; it details a long, cruel life of unpaid, indefinite servitude and physical and emotional abuse of one domestic helper.

I’d love to say that Lola’s scenario is rare, but we all know the truth: it’s pretty common here, and we’re dicks for continuing to perpetuate this culture well into modern times. Meanwhile, other people—in this case, non-Filipinos—are angry at Tizon and The Atlantic for publishing his story and what they perceive is the humanization of a “slave owner.”

Read “My Family’s Slave” &I just literally wanted to reach into the story and punch every fucker in the Tizon family, including the author.

— ✡️Josh Shahryar ☪ (@JShahryar) May 16, 2017

Just… hold the fuck up right there, guys. The indignance at the crimes committed in this situation is welcome, but a lot of the international outrage is coming from a place where they don’t fully understand the culture the story is set in, and that just makes all the anger and lecturing feel like we’re being talked down to. Let’s try to unpack this as calmly as possible, because there is a lot to get through here—not only for the foreigners in the conversation, but as well as for the locals who need to deal with their own feelings about this particular facet of our culture.

1. There’s no defending the elder Tizons’ behavior

They were shitty, and it was their behavior that incensed me personally. People should also understand that Alex and his brother had a hard time fixing these issues, but because of the way a Filipino (or Asian, in general) family is—oftentimes strict, overpowering, suffocating—it’s often hard for the younger generation to do that. It’s so easy to say he could’ve done more. It’s always easy to say that.

I look at Alex’s piece as one final act of contrition, as a way to process and work through all the emotions he’s had, after he did his best to give his Lola a better life once she was freed from his mother. He confronted his mother’s entire character the only way a son can, with both the good and the bad. I’m sure he passed away with guilt in his heart, a whole lifetime’s worth, and his last gift to Lola was to tell her story and make people aware of these injustices that happen.

2. This is a thing we’ve carried over since ancient times

Filipino families having domestic helpers is just a thing here that’s unfortunately part of the culture. In theory, they’re supposed to pay them properly, especially in this day and age, and treat them like human beings—as actual employees, not chattel. But let it be made clear that we are in no way saying that this is a thing we should continue to perpetuate, and it’s a damn shame that circumstances around here are so terrible, poverty and inequality so bad that people need to go take these jobs just to live. And that there are people still rich and powerful enough to make other people serve them.

@ironmima @gigidensing Predates it, as article itsef pointed out. eg The different types of alipin. pic.twitter.com/aB9auOuzi5

— Manuel L. Quezon III (@mlq3) May 16, 2017

Yeah, it can’t be denied that there are still families who still think they’re slaveowners and treat slaves like shit, but it’s still not quite the same as American slavery. Our colonizers have also hijacked the slave culture, twisting the knife even deeper. While the thing that happened to Lola (and much worse) still happens now, a good number of them do it voluntarily, for important reasons.

3. This is something we need to deal with ourselves

If you’re outraged as a non-Filipino, it’s mostly because you don’t know that this is the case here, that many people here choose to work for other families—not just because families need help, but sometimes it’s the only way out to get a shot at a better life. This is pretty much why Lola had to go work for the Tizons: it was a way for her to have a relatively more comfortable life. The harsh reality is perhaps it might have been the only way at the time.

Meanwhile, we’re mad at ourselves, and the article also sobered us up. If we’re moved, it’s because it’s something that’s still happening, and we’ve been ignoring or overlooking for one reason or another. And if it’s viral now, then it’s only because we’ve finally (hopefully) started taking a look at ourselves, if we’re at least treating our help as the human beings they are.

We don’t need non-Filipinos to preach about how slavery is terrible and all that, because we get it. You clearly mean well, but at this point the imposition of your own completely different perspective is unnecessary and highly uninformed noise that isn’t helping the issue. Allow us the agency to fix this moral issue ourselves, because we’d like to think that we’re civilized enough to have this conversation here. Don’t hijack this from us.

4. It’s okay to think something is written well and still not agree with it

Just a personal point of contention. Moral disagreements doesn’t change good writing, and being moved.

So take this story as a mirror to hold up to yourselves, especially if you’ve got helpers. Let’s hope your family isn’t as bad.

Editor’s note: This article has been edited to reinforce the fact that the author and Scout don’t condone the Filipino culture of indentured/forced servitude in any way. We apologize for any misunderstandings the original version caused, promise to continue producing content to the best of our ability, and welcome all attempts at discourse and discussion over anything we publish.

Comments